(Note: This piece was bought by Harper's Magazine first, then (in 2010) by Virginia Quarterly Review; both magazines sat on the story, then killed it, for reasons that remain unclear. Be that as it may, it's still a good piece, albeit long.)

The piracy zone is well defined in all dimensions.

Geologically it is carved out to the west, south and east by the boundaries of tectonic plates. The Sunda Trench thrusts in a curve from northern Thailand along the west coast of Sumatra to the tip of New Guinea; there it kicks against the Philippines Trench that runs to the northern end of Luzon. Behind the trenches, the Pacific plate shoves west, the Indo-Australian east and north, converging on a theoretical center just to the north of Borneo.

The coasts of China, Vietnam, and Malaysia cap the zone defined by these trenches, giving it the shape of a rough heart.

The geographical and biological dimensions of the area are harder to separate. This is the planet’s largest, most intense tropical archipelago, a fretwork of over 20,000 islands and uncounted headlands, deltas, reefs, swamps and other types of stitching between sea and land. The marine environment takes the form of a pivot of currents spinning counter-clockwise around Borneo, powered by the thrust of the Northern Equatorial Current moving toward Africa above, and the Equatorial Counter-Current rolling to Hawaii below.

The zone’s biosphere, known to marine biologists as Sundaic Southeast Asia, contains a diversity of marine life unmatched anywhere on the planet.

The human aspect of the zone, finally, flows from its other elements; for in this pulsing of tepid seas, soft winds, deep jungles, regular rainfall and mountains rising like surprised gods into the roof of clouds, it is taking the path of least resistance to catch fish, build boats, and sail, using the volcanoes as marks by which to measure both your navigation and your philosophy. And the early settlers of piracy zone were similar enough in how they moved—at risk and in boats—that some have posited the existence of a single Austronesian people who sewed it together with their relationships of piloting and barter much as mangrove lagoons form a junction between the two principal elements of the zone.

This is the place the ship enters now.

She is a bulk chemicals carrier of 6000 gross tons with three decks of accommodation aft, a single derrick, a Makita diesel. Like scores of similar ships she was built in Japan in the 1980s and has plied the waters from India to Korea almost continually since, trading under a half-dozen different flags and owners. A dozen skins of paint of various colors flake off now to betray her history as well as the enduring truth of rust beneath. Her crew includes Malays, Thais, Indonesians. The skipper is Singaporean; the mate, Malaysian Chinese. Now, at 3:20 in the morning on a calm March night, the mate and a deckhand stand watch, checking the radar for other ships traveling the strait. No one else is awake. The cargo, 6,000 metric tons of palm oil, sloshes gently as the ship rolls northward toward the waiting boat.

It is the boat that will complete the circle of geography and trade in the unnatural yet in some ways logical act that is the violent takeover of a vessel on the high seas. In this part of the zone she is called a sampan, though in other areas she might be termed tempehr, bombot, go-fast. She has a fine bow, a narrow beam across which the men sit, their weapons in their laps. Two 60-horsepower outboards burble at the stern. Her crew in its composition is not unlike the freighter’s: Indonesians, Thais, a Chinese; the zone has ever preyed on its own. One man nervously handles a coil of line with an iron grappling hook, wrapped in tape, tied at one end. Another holds a mobile phone into which he murmurs details of the ship’s profile as she comes abeam, then proceeds on her northward course. He nods to the man handling the outboard. The helmsman gooses the throttle, swings the sampan at fifteen knots, and lays her, three minutes later, against the ship.

The rope-man man throws twice before the hook catches on the main deck railing. He holds the line taut while five men with carbines strapped to their backs and machetes at their waists climb hand over hand to the rail and drop into the maze of line and ventilators. One stands guard by the rope; the other four climb to the wheelhouse. The mate and deckhand do not move as four figures in balaclavas and dark clothes burst like bits of typhoon inexplicably dropped into their personal weather from both wings of the bridge. The intruders scream in Malay, Get down, Don’t move, Do you want to die now? and wave their arguments of small-caliber death. The rest of the crew is rounded up and locked with the watchkeepers in a cabin.

The diesel rumbles, unchanged. A container ship looms and disappears, unaware, to the south. The man with the cellphone checks the charts. Two hours from now he will order a change of course and the ship will veer from the shipping lanes and into the wilderness of islands and peoples surrounding. Later still, the crew will be put ashore on an island so isolated it must take them days to reach a radio. By that time the ship, like so many others before her, will have disappeared into the piracy zone, and the odds are fine that in her present form and under her current name, she will never come out again.

#

It is to find out what happened to this ship and others like her that I first enter the zone. My first step in that direction is on a tangent, from New York to London, to talk to people from the International Maritime Bureau, an organization that collects information about modern maritime piracy. It is based in Barking, outside London. I have corresponded with the IMB for months, and two weeks earlier I arranged to meet its director, Captain P.K. Mukundan. When I arrive on the agreed date at the group’s office, his secretary tells me Mukundan is in Dhubai. I interview his deputy, Capt. Jayant Abhyankhar; seething a little as I stare over the pubs and chip shops of Barking High Street. Then I realize it doesn’t matter whom I talk to here. Good stories are icebergs, with a fraction of their mass above water. Mukundan made it plain over the phone that he was not going to give me underwater data, but only the visible stuff: the numbers, the pie-charts, the press releases.

The visible stuff is dramatic enough. Modern maritime piracy—by its most basic definition, the violent robbery of vessels at sea—constitutes a major international industry whose worth in 1999 was estimated at $22 billion. 202 incidents of piracy were reported worldwide in 1998, involving 78 deaths. In 1999 there were 285 incidents and 3 deaths. No figures are yet available for 2000, though the number of incidents so far indicates no downturn, and the apparent hijacking in February of the Hualien 1 with her crew of 21 would, once confirmed, bring the death count up relative to last year.

By far the greatest number of piratical events take place in the zone. 267 hits have occurred within its boundaries since the beginning of 1998. Abyankhar once served as watchkeeping officer on Indian freighters. His eyes betray nothing as he describes the difficulty of catching pirates. Officials in Indonesia, the Philippines and China, he says, are being bought off by pirate syndicates, or conspire with them from the outset. A country’s legal system, in dealing with a ship registered in Panama, crewed by Indonesians, hijacked in Filipino waters and seized in China, is so unequal to the task of prosecution that often the authorities will simply drag suspects to the nearest border and throw them out. Shipowners faced with a lengthy court case while their vessel, impounded as evidence, sits in port at a cost of $10,000 a day, find it cheaper to drop charges, write off the cargo, and take up trading again. The IMB’s piracy center in Kuala Lumpur has many details of such cases, Abyankhar says. Its director will be expecting me. Like Abhyankhar, he will be unable to furnish me with details.

I no longer take notes, having already lost interest in statistics and teflon offices that possess nothing of what is vital here; not a whiff of diesel or red-lead paint or the stink and grind of cargo; none of the loneliness, the occasional panic, the sudden intrusion of violence on the loneliness of a night watch. What I need is to talk with men who have lost their ships—or boats, for pirates operate at all levels of the spectrum. I want to know, in the gut, what it feels like to sail waters where the next hull coming over the horizon may be a fast vessel full of men bent on robbing your ship and killing you if you resist. I admit that what I want also to find is what lay behind stories I read as a kid: Blackbeard and Golden Vanity, the sham and cutlasses, the adventure theatre of boyhood. What I want is to get taken by the zone.

I have a side-angle on this story to use as cross-reference on both its historical aspect and my ability to sort out the hype from the hidden lineaments. I travel the Underground to Pimlico and walk to Bessborough Gardens. It’s a three-sided square of Regency houses framing a rectangle of grass and elms off the smoke and traffic of Vauxhall Bridge Road. Joseph Conrad sat down to write his first novel, Almayer’s Folly, at 6 Bessborough Gardens. Almayer’s Folly had many flaws but it also contained the mix of maritime accuracy and emotional charge that was to set Conrad’s later work apart. It took place in eastern Borneo, near the epicenter of the piracy zone, in a human environment to which piracy and its cousins—smuggling, corruption, insurgency—form the background. I have a gut suspicion that Conrad, who may have run guns on the Spanish frontier in 1877, was involved in the background more deeply than he let on.

But the house numbers here are out of synch. I walk around, buttonholing locals, for fifteen minutes before I learn these buildings are expensive fakes, part of a development built, under the patronage of Prince Charles, to mimic the architecture of Empire. The house Conrad lived in was destroyed twenty years ago. I smoke a cigarette under an elm, wondering what of hidden history can survive the opposed brutalities of indifference and nostalgia.

#

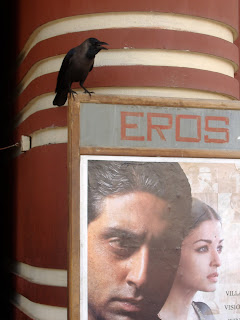

Singapore. In a way, Bessborough Gardens held a lesson for approaching this city, which resembles nothing so much as downtown Dallas. Among the glass skyscrapers, the Ramada architecture, the swirl of accountants, some vestiges of continuity remain: a row of Malaysian-Chinese counting-houses thick with shadowed balconies; a temple of automated worship, fat glass Buddhas lit by electricity from within, prayer columns driven by motors twinkling amid the joss-smoke. A work crew of Malays clad in sarongs drifts by. I check in at the mariner’s hostel, using my old merchant navy discharge book. Here I may catch hold of strings of rumor about ships that disappear, or off-color opportunities for waterfront work that might lead to information. I tack up on the notice board a sign offering the services of an experienced seaman, any line of work considered. The desk clerk averts his eyes. [fn]

Singapore is the busiest port in the world in terms of ship movements. From the Cathay Airbus, flying in, the anchorage looked like a pattern of ermine, and each dark score a ship; bulk, general cargo, sampan, container, coaster, tanker, Very Large Crude Carrier, Chinese tongkang, everything on either side and in between moored or maneuvering in the electroplate of sun and sea and desultory cloud-shadow. In the city you find evidence of seafaring on the brass plates of upstairs offices bearing the names of ship’s agents and maritime trading companies. I study these names with the hot gaze of a paranoid, wondering what conspiracies lie locked behind the airco and mahogany. The lawyers and insurance investigators who research the more organized forms of piracy state firmly that the trade is indeed structured in “syndicates.” These are specialized maritime criminal groups consisting usually of three principals: a financier with cash to invest and a buyer in mind for whatever cargo or ship is being stalked; a mechanic, responsible for hiring assault crews and riding teams, and arranging false papers; and a producer, a man (it is always a man, in the world of maritime Asia) with a foot in the various environments, who brings investor and mechanic together, and makes everything work. On an island across the Singapore Strait Indonesian police have in their custody a Chinese pirate, known only as “Mr. Wong,” who most likely filled the role of mechanic.

Investigators such as Clay Wild of Western Pacific Marine or Andrew Horton of Richards Butler in Hong Kong have differing theories about who fulfills the various roles of a piracy group but they are unanimous about one aspect and that is, all these men are intimately involved in the hermetic world of seagoing trade. They most likely are traders themselves, or brokers, or ships’ agents who arrange the details of docking fees, pilot dues, crew advances; who know down to the last detail the greasy and unromantic incunabulae of cargo. Given the web of links between pirated ships and this city, given what the investigators have learned, it is certain the syndicates are present in Singapore.

But the brass plates tell me nothing; these syndicates live in the dark. Singapore itself is a slut for the New Asia, that sterile mix of Confucius, Yahoo! and Nick Leeson; and it’s hard to get New Asia on the line. Contacts don’t call back; a few arrange interviews for much later. John Chang, a police spokesman, assures me with some asperity that “There is no piracy in Singapore.” I never meet the Piracy Center director, who leaves abruptly on a two-week trip. Singapore harbor has been sliced into giant container terminals inside secure areas that allow no pocket of seedy bars in which to get hired by operatives of whatever group is shaping up a hit at the time. What has happened to Singapore is what happened to Times Square. Because the vaster schemes of high finance rely on an appearance of probity, the smaller and obvious sleaze must be squeezed from the neighborhood. In New York, it moves to the margins, to Tenth Avenue.

In Singapore, it goes to Batam.

You know at once you are not in Singapore when the ferry, zigzagging among fat tongkangs, docks at Sekupang and you step into the drop-forged heat and are assaulted by exhaust and thin brown men shouting for your attention. I hold back, asking the customs men for info about the syndicate pirate held on this island by the Indonesian authorities. Studying the touts, I spot a taxi-driver who seems more laid-back than the rest, and point to him, feeling very much the gwailo. His cab is one of those box-shaped vans the Japanese reserve for Third World use. He says he speaks good English. His name is Amin.

It turns out Amin’s English is not so great but with my five words of Bahasa and an English-Malaysian dictionary we get by. There are two terms for pirate in Malay: pembajak, and badjao laut, which is also the outsiders’ name for the Sea Gypsies of southern Asia. I tell Amin I want to find “Mr. Wong.” “Pembajak,” he repeats, smiling. “In Batam, plenty jungle, plenty girls. Plenty pembajak.” Amin is a Protestant and a Batak; a member of a tribe from northwestern Sumatra. He has an easy smile and a real curiosity about what I am doing. To him I represent a change from the usual visitor from Singapore who, he says, is interested only in whores. “Pembajak in village, by the shore, I show you.” Amin looks at me sideways. He has access to a deep network of Bataks living on the island, and those contacts will stand me in good stead, but in all the days Amin and I hang out together he will never quite shake off the suspicion that what I really want is sex, and that eventually I will come clean and hire one of the thousands of call-girls who ply their trade on the island. That first day he drives me to the Batam Industrial Development Agency, a body charged with supervising the selloff of this chunk of Indonesia to the highest bidder. Mr. Wong is famous on Batam. The people at BIDA know for certain he was sent for trial to Jakarta, but with the grace typical of most Indonesians I meet, they suggest that we first check Batam jail.

The sole jail for Batam’s 300,000 inhabitants is a low building of peach-colored stucco with the usual Tiki gable in front and not a trace of barbed wire or watchtowers. A Judas opens in a green steel gate and we are allowed inside to stand among a crowd of guards smoking clove-scented cigarettes, while Amin explains what I want, and in a large room to one side prisoners hold babies, hug girlfriends, and stare at me.

The jail commandant is named Frandono. He is a quiet man with the face of a suffering semiotician. Frandono has published two small English/Bahasa dictionaries of correctional terms. He offers me tea. He asks me if it’s true that Alcatraz was decommissioned, and seems disappointed when I say it was. He tells me Mr. Wong was in Jakarta last week for medical reasons but now he is back. If I can get permission from his lawyer in Nagoya, the island’s main town, I can interview Wong tomorrow. “Mr. Wong is a pirate,” Frandono says, “he is in the syndicate [hierarchy] but he is very low. I think the navy is falling down [on the job],” he adds. “The syndicate pays the navy to say he is the chief.” As I leave Amin excitedly pulls me aside to talk to a guard. The guard claims to know a member of Wong’s gang who is still in the trade. He can arrange a meeting, maybe tonight. Amin nods vigorously. He can vouch for the guard, who is a neighbor in his village.

We wait in Batuaji. Amin’s “village” is a shantytown, a ghetto of tin-roofed shacks without sewers or running water. Only part of it is electrified. As many people live in Batuaji, Amin says, as in Nagoya and I can well believe him. The shantytown sprawls far on all sides and only to the south can I discern a horizon of jungle from which the place was hacked. Amin’s wife serves us tea while their five kids and much of the neighborhood crowd into the shack because Amin has power, and a television. Tonight a popular Mexican soap opera is playing. Waiting in Batuaji then—waiting in other places on Batam as well—I begin to understand that the island has become an Asian Tijuana. It is a place where Singaporean and Western capital flows to take advantage of cheap Indonesian labor, and where men and women converge from all over the archipelago for jobs with companies like Sony and Matsushita, or with shadier businesses that thrive in the Lion City’s shadow.

Except most don’t find jobs. Instead they land in Batuaji, squatting in roadside stalls, smoking as the sun hammers down and the motorbikes whine by loud and ceaseless as the hornets of hell. Amin grows nervous as we wait. He realizes, thinking back on what the guard proposed, that the place where we are to meet the pirate is a kampong, or hamlet, in one of the surviving jungle areas of Batam. He thinks, now, that to meet pirates there might be dangerous. We return to the jail and stand in the shadows outside most suspiciously. The guard shows up, late and dejected. The pembajak has left the island and won’t be back for a month. Amin grins in relief.

Batam is close enough that I can commute to Singapore; spend an hour or two in the morning making calls, then zoom back to Sekupang across the silken swells of the Phillip Channel. Ships run on all sides, and the ferry dodges them at twenty-five knots. In the two dozen trips I take across this stretch of water I see each time a minimum of ten large commercial ships transiting the strait. Only thrice will I cross without sighting a tanker of 100,000 tons or more. The conventional nightmare, fostered by IMB in particular, is that a band of pirates will hijack a ship and put it across the bows of a supertanker, or even take over the tanker and lose control. But such a disaster is unlikely; the pirates so far have been professional and the tankers they go after—the tanker Mr. Wong went after—are small coastal ships, the workhorses of the zone.

The tanker Mr. Wong has admitted to hijacking was called Petro Ranger. She flew the Malaysian flag. She left Singapore April 16, 1998, with a cargo of 11,615 tons of diesel and kerosene, bound for Ho Chi Minh City, and her rendezvous with Mr. Wong.

Mr. Wong is not his real name. The prisoner of Batam jail carried a Singporean passport in the name of Chew Cheung Kiat, but the Singapore authorities swear the document is false. Press reports in Singapore claim the passport belonged to a dentist, or alternatively to a Singaporean day laborer who was pickpocketed in Malaysia. The implication here is “of course Malaysia;” besides Batam it’s the other cesspool of crime lying alongside Singapore the Clean. But I will continue to think of him as “Mr. Wong,” it is part of the scenario everyone has built up, Singaporeans, Indonesians, Mr. Wong himself. And the Indonesian Navy says Mr. Wong owned a ship, a 399-ton coastal freighter called the Pulau Mas, which he anchored in areas his victims would transit. And when the Petro Ranger approached, shortly after midnight on April 17, the crew lowered a speedboat, and they snuck up on her. The ship’s captain, Kenneth Blyth, told Lloyds Maritime Asia that the pirates held machetes to his head and groin. They used cellphones. They knew Blyth’s home address in Australia and threatened to harm his family. The pirates spoke Bahasa. The cargo was transshipped at sea, which implied serious competence on the part of the riding crew. They took Petro Ranger to Haikou, in south China; there Blyth escaped, and raised the alarm.

Frandono gives me the name of Mr. Wong’s lawyer, in Nagoya. The lawyer, whose name is Dahlan, tells me a team of Japanese television journalists will be arriving two days from now. He suggests we interview Wong together. I am starting to get nervous about the amount I am spending, not only in ferry ducats and taxi fees but in time. The feeling I got in Batuaji returns more and more as Amin and I scream down the cracked asphalt and red-dirt tracks of Batam, courting disaster at the hands of the psycho traffic on this crowded island, never wearing seatbelts because to do so would clash with the macho ethic of this place and also, and consequently, they don’t work; thinking how Westerners fuck up the East with their sense of time, their insistence on an immediate, mechanical cause and effect, like gunboat A arriving at kampong B to demand treaty C; or like a writer parachuting into this complex society and demanding to see real pirates now, get this week the story he came for. And what the East has over us is, in such linear terms we will only find a temporary treaty, a one-dimensional story. But we scream around anyway, to the navy first, its base sandwiched between the offshore-oil-rig assembly plant of the McCormick Corporation of Corpus Christi, Texas, and Sameon—a shantytown that Amin tells me (looking at me sideways) is populated exclusively by call-girls. The base resembles a set for South Pacific: bungalows, a flagpole, disused minesweeping drogues, chicken shacks overlooking palms and mangroves and the lapis strait beyond. But what impresses me most about the base is not the setting but the casual arrogance of the officers. They order Amin to button his shirt to the collar before speaking. And I mark the extreme nervousness of my driver. Amin tells me later that he avoids this base because even under the current civilian regime the military still do pretty much what they want and if they don’t like you, you can still disappear and there is little anyone can do about it.

The uniform of the base commander, Captain Budhi, is crisply ironed. His face, behind tinted glasses, is excitable as a slab of limestone. He finds out quickly what type of writer I am; it is not the type he likes. He gives me tea and clove cigarettes. “Where is your clearance?” he asks politely. “What clearance do you have in your country?” I assure him, untruthfully, that my security rating is A-1. He smiles grimly and says in that case I will have no trouble getting the admiral in charge of security in Jakarta to give me clearance, as the Japanese TV men did. The interview depresses me. I wonder if I am the wrong type of writer for this story, though I consciously decided not to go the journalistic route, to avoid the official tour scheduled and nailed down from New York.

Budhi tells me something beyond the party line. Mr. Wong’s ship was impounded after the arrest and now lies a couple of miles from here. He gives me permission to take pictures from shore. The ship, it turns out, is anchored with a gaggle of other coasters off a two-man naval station harboring the idle and gray-painted outboards that are the only Indonesian naval presence I will ever spot in these waters. Amin tells me as we jounce down the dirt track that this beach is known to the locals as “Pantai Stress,” or “Stress Beach,” because it’s fairly secluded and dating couples can come here, as he puts it, to get away from the strains of life on Batam, and to indulge in “imaginings” as they stare out to sea. The navy station radios Budhi to check my clearance. Amin and I walk to a coffeeshop built on pilings over the lagoon, passing a crowd of dark men—I mean, they are dark, they glower darkly and hang out by a black, upturned sampan, caulking the seams—and I think: Here are the raw recruits of piracy gangs, unemployed fishermen, beach dwellers owning a fast boat and a bad attitude and not much to lose beyond. We hire one of their sampans to go to the Pulau Mas.

She is an old coaster with her homeport, “Pnomh Penh,” roughly painted on the stern. The name of her previous port, Hamburg, is visible under the paint. She lies, down by the stern, with hatches open and every inch rotting under the hard sun. A frayed rope ladder hangs down the starboard side. After a quick negotiation our skipper sidles up to the silent ship and I clamber aboard in a clumsy pantomime of what her crew did to the Petro Ranger. I go straight to the bridge, as pirates would. I figure I have only a few minutes before the navy susses out what I’m doing. The wheelhouse is a mess; binnacle and wheel have been removed and hydraulic steering oil slicks the deck. The radio room is a jumble of charts and notations and I thrash through them, sweating. My theory in coming aboard was a function of noir thrillers where the maverick gumshoe, visiting a scene the cops already tossed, picks up a chewing-gum wrapper on which is scrawled the phone number of the killer’s favorite bar. There are no gum wrappers but I find a logbook, thick with positions, and it strikes me as odd the navy would leave this behind. I stuff it under my shirt, with a crew-sheet listing a ship’s agent, Leong Shem, in Singapore. I roam around as much as I dare but the decay of this ship is getting to me. It may only be the navigational sanctimony of one who has worked on ships and depended on them for survival but something feels bad about this rustbucket, she feels dirty and lost and wrong. I slide fast as I dare down the rope ladder and the navy notices none of it.

More waiting; and Amin takes me to a place where waiting is the point. It’s a kopitiam, or coffeeshop, located off the main drag in Nagoya. Nagoya is the most Tijuana town of this border island, a pinball whirl of concrete commercial blocks called “kompleks” with tiny shops and markets wedged between, surrounded in turn by the impenetrable circuitry of people, on foot, on motorbikes, on “tricycles,” which are motorbikes with a cab riding a third wheel. But it’s a good place, the Kopinda, a shaded joint splayed on the corner of a kompleks, with white tiled columns and cement floor and great red adverts for Tiger beer, and stalls along the wall selling satay, fried fish, and noodles. Kopinda means “good coffee” in Bahasa. It’s a place where seamen sit, waiting for jobs, hanging out at the cheap tables like question marks silhouetted against the furnace streets—getting up suddenly and disappearing for no good reason, only to show up later and sit again.

I spend hours at the Kopinda talking with Amin and, increasingly, with contacts he has arranged. I spend even more time sipping tea in silence, moodily smoking clove cigarettes, of which I grow increasingly fond. I think thoughts whose underlying structure, like the Pulau Mas, feels somewhat altered by the hard sun. The Boy’s Life aspect of this story bothers me. I wonder why a trade so dingy and desperate, so founded on misery and death, should enjoy such swell PR. When I phoned my daughter two nights ago I found her growing increasingly upset by the length of my absence; but the fact that I was running around looking for shady characters remained a mitigating factor, because they were guys in bandannas and eyepatches brandishing curved swords—piracy, for kids, being largely a fashion statement. The argument Emi made was not that I shouldn’t leave her to chase pirates, but rather that I wouldn’t succeed: as she put it, “There are no pirates in Hong Kong, there are no pirates in Tawi-Tawi” (an island near a strait off Borneo I told her I would visit), “and most of all, there are no pirates in Singapore.” As I sit in the Kopinda I wonder if part of the cheerful spin piracy gets in Western culture doesn’t come from a nostalgia for the kind of broken time-frame pirates represent, in the sense that they live on the fringe, outside normal schedules; on the sea, which is already a margin. European pirates, like fishermen, often created an egalitarian shipboard society based on shares of the profit, which set them apart from the autocracies of their day. [fn]. And these men thrived on fucking up Western time-frames: boarding ships whose schedules were regimented, even in the eighteenth century, by markets and chronometers, kidnapping their passengers; ripping them out of the standard day. So that we, controlled and rendered impotent by the deadlines imposed on us by jobs, airlines, governments and other unstoppable forces, look at those Howard Pyle paintings of guys kicking back forever on sunwarmed decks and think, Why not?

Kopinda’s clocks, it turns out, are set to piracy time.

Hassan is a gangster who looks the part. He’s built thick as a mangrove trunk. His eyes are mean as a cobra’s. He knows people in the trade, in particular a former crewmember of the Pulau Mas. Through Amin’s Batak network I meet Rony Pangaitan, who looks like Omar Sharif and is a chief in the Batak tribe and a politician honest and true; such an animal is rare in Indonesia. Rony is a town councilor and an activist for PDI, the reformist party led by Megawati Sukharnoputri. Through the Batak mafia and via his job, he knows a pantload of people. One of them is a pirate named Jahin.

But in the meantime the meeting with Mr. Wong happens. The Japanese TV reporter is clearly the mainstream type; he has a briefcase full of permits from Jakarta. The Japanese public has thirsted for piracy news ever since the Tenyu, a Japanese ship, was taken by pirates off Sumatra in 1998. I hear later from Rony that Mr. Wong went to Jakarta last week for arraignment, and tried to escape. Two “interpreters” assigned to the Japanese mutter darkly about my clearance and place last-minute calls to the capital. A prison officer tells me they are BIA, or secret police. When I interview Mr. Wong, or Chew Cheng Kiat, or whoever he is, I get no sense as to which of his names or stories are true. He is a thin Chinese man in his late fifties with close cropped hair and an amused expression that only once reacts to the brilliantly tricky questions I pose him. It’s when I ask if he has ever heard of the Leong Shem Shipping Agency. He glances at Dahlan for a second or two, looks at me calmly, and says, “No.” Mr. Wong signed a paper confessing that he was a pirate who conducted attacks on seven different ships, including the Petro Ranger; now he denies it all. He tells me he was a lowly ship’s agent in Singapore. Pulau Mas belonged to his buddy, Mr. Ng, a businessman in Johor Bahru, the Malaysian port just north of Singapore. Mr. Wong had no idea what Ng or his ship were up to. He was arranging a delivery of fruit to the ship when the Indonesian Navy came out of nowhere, in Malaysian waters, to arrest him and seize the vessel. Dahlan tells me later that Mr. Wong is in fact a professional pirate, but he takes orders from a certain Ah Ling and a Mr. Tan, who are higher up in a syndicate financed by mainland Chinese money via Hong Kong and Singapore. Remembering how Mr. Wong smiled gently and dodged questions, I think of all the different versions of his tale: how the ship was in international waters, in Indonesian waters, in Malaysian territory; how Mr. Wong is the syndicate’s mechanic, or the producer; how he is Singaporean, Indonesian, neither. How he went to Jakarta for medical reasons, for legal reasons, to arrange the sale of his ship. I think of the braided lines of conspiracy and motivation in Almayer’s Folly, and remember, like a curse, the Kipling epitaph: “…a fool lies here, who tried to hustle the East.”

The next day, back at the Kopinda, I finally manage through a lot of bullshitting and buying lunch for people to meet the other crewmember of the Pulau Mas. We conduct the interview in Amin’s taxi, just like G-men I think, stop-going in the vicious anonymity of Nagoya traffic. Though I promised not to use his name or rank, it’s OK to say this crewman belongs to a culture traditionally known in the zone for crewing pirate ships because there are a dozen tribes that could be described that way. He has the hands of a seaman, half curled as if they can never be at rest until they touch and deal with a vector of pawl, shackle or cable. I ask him about details of equipment I saw on the Pulau Mas, stuff only someone who worked on the ship would know. His answers check out. He, in turn, confirms that Mr. Wong—who he says is not Indonesian, by his accent, but Singaporean or Malaysian Chinese—is indeed part of the “syndicate” that ran the ship. He is probably the “mechanic,” and definitely a firewall, whose job it is to take the blame and keep his mouth shut in case of trouble. The gang’s “producer,” this crewman claims, is an Indonesian named Mike. Then he furnishes yet another version of the arrest of the Pulau Mas, which is that Wong and the skipper had not forked over to Mike the profits of a recent hit, so Mike got some of his navy buddies to motor into Malaysian waters after dark to lean on them; at which point demands were made, threats followed, and the navy ended up busting the ship, and Mr. Wong, and those crewmembers unlucky enough to be aboard when all this came down.

“Mike” was not arrested. In fact, he recently offered my crewmember a job with a different gang of pirates shaping up for a job in Indonesian waters in the near future. My crewman turned him down; he says he has given up piracy for good.

Still seeking anonymous zones we drive to a canteen in the Batam Industrial Park, where workers from the various factories come on break. The park is 320 hectares in area and employs thousands of workers, most of them female. Yet this is only a small percentage of the total maquiladora aspect of Batam. For the island, which as late as the 1980s was a backwater of 7,000 inhabitants inhabiting a handful of fishing villages squeezed between jungle and sea, in the late ‘80s and ‘90s was engulfed by the twin dragons of Singapore’s regional expansion plan, and the fiery corruption of Indonesian politics. Suharto donated the island, administratively speaking, to Pertamina, the state oil company, and put his buddy Habibie in charge. Habibie set up a system hardly unknown elsewhere in Indonesia: Give massive tax breaks and cheap land to your family and buddies and multinational companies; receive, in exchange, large chunks of cash. The beneficiaries included Habibie’s son Thareq Keemal, his brother “Timmy” Abdulrachman, and his pal, Liem Soe Lieng. All have interests in the company that set up the industrial park, which rents space to Schneider and Novartis, among others. Watching the lucky workers at the Batamindo canteen—lucky because they get paychecks, while most on the island do not—I am swamped by the realization that this piracy I am looking into is picayune and low-rent compared to the vaster hijackings practiced by fat cats and corporations on this stretch of coast. Much as, I suppose, the depredations of Bellamy, Morgan, and Tews were as fleabites compared to the orgy of bloodshed and pillage, known as the European colonization of America, on which they preyed.

In Western time I make arrangements to meet Jahin, a contact of Rony’s who lives in what Rony describes as “a village of pirates” on Belakangpadang Island. There he practices the garage-startup version of the trade: holding up passing ships, forcing the ship’s safe and stealing any proximate valuables, and vanishing into the night. I also spend whole days in Singapore and this is the worst time because I am not getting anywhere, and at the same time I am making plans to travel to the strait I told my daughter about, the one separating Borneo from the westernmost islands in the Philippines. I want to ride with a snakehead across that strait, for it’s a piece of water known for being hit on by pirates, who usually just hold up illegal immigrants making the trip, but who have been known to kidnap passengers, machinegun everyone on board. The odds of this happening are not huge, but it still makes me nervous. Yet how else do I get close to this issue? How else do I locate the story’s nub, and learn in my gut what piracy is? The thought of my family trusting me to research this story and come back whole while instead I risk my life and their happiness, however marginally, conjures bad dreams in the Singapore “Mariners’ Club:” facile visions of racing across cruel waters with an invisible something in pursuit. It would be safer to track down one of the producers or mechanics who work out of Singapore or Hong Kong; show him evidence of what he did, perhaps convince him to talk. For a few days I think I might be able to do this. A lawyer in Hong Kong points me to a writ in Hong Kong High Court, Action HCCL 27/1999 of February, ’99, that names the Poa Seng Shipping Company of No. 20 Lorong 21/A, Geylang, Singapore, as owner of the 15, 788 barrels of palm oil transported on the Pacifica. This was a ship that got pirated on a voyage between Pasir Gudang, Malaysia, and China in June of ’98. The Poa Seng company is also named, in an action filed in London in late 1999, as owner of a cargo that disappeared in similar circumstances on the Jubilee. It might be total coincidence that the Tenyu, which was hijacked by pirates and then showed up in southern China under a different name in October, 1998, was carrying 15,788 barrels of palm oil of the same quality as Pacifica’s when she was busted. It could be coincidence that two of the pirates on the Tenyu were also involved in the case of the Anna Sierra, a freighter full of sugar hijacked off Indonesia in 1995. It might also be coincidence that the owners of the Jubilee were listed as Mr. Ng and Mr. Tan, two names that came up in connection with Mr. Wong’s group. One has to remember that in southern Asia Ng, Tan, and Wong are names as common as Brown, Jackson or Jones in the U.S.

I’ll get no hard answers from Poa Seng, however. Its address turns out to be a beauty parlor. Its spokesman, Lee Ha Seng, when I finally reach him on the phone, tells me he has no knowledge of the Pacifica, or the Tenyu, or of palm oil cargoes. He says his company is not involved in shipping anymore. Then he hangs up; further calls go unanswered. I squelch through a downpour on another morning to locate the Leong Shem Shipping Agency, of IIA Stanley Street, listed agent for the Melaka Jaya; this was the name Wong’s ship went by before she became Pulau Mas. If “Mike” and his bunch are shipping insiders, I theorize, it is likely they contacted friends or even co-conspirators to find a cheap vessel to use for hijacks. But no shipping agencies rent space at IIA Stanley Street. And the cool, computerized records office of the Singapore government, located on the eight floor of a Ramada-style tower on Cecil Street, holds no trace whatsoever of a company named Leong Shem.

My last gambit consists of tracking down a “Captain Joe Pulaka,” whose name appears on the Pacifica’s papers, and came up in connection with the Jubilee. A man in the maritime insurance business tells me that I can find Captain Joe through the consulate of Honduras, the Central American country that arranges registration papers for shipowners who don’t want to pay high fees or answer too many questions. A large proportion of pirated ships have found new identities under the red, white and blue colors of Honduras. I put together the specs of ship not unlike the Melaka Jaya. Then I knock on the door of Marden Marine Management, which doubles as the Honduran consulate. The consul is a Singaporean named Allen Walters. He is in his early fifties, with a square mustache, very white teeth, lots of rings. A thin grin appears on his lips as soon as I mention my old buddy Captain Joe and never quite goes away after. He tells me Joe has not been around for a long time. Joe, the consul adds, with a sorrowful shake of the head, has come under the spell of the dark powers of the waterfront. He seems, in particular, to have trafficked Honduran papers for ships that it turned out later had been taken by pirates. But enough about Joe, Walters continues. Then he explains, in great detail, how for $5,000 Singaporean dollars I can obtain a 90-day temporary registration certificate for the used coaster I am purchasing. All I will need is a certificate of sale with an affidavit from a notary public in Malaysia, which is where my fictional ship lies. After that, as others have done—and Walters does not say this—I can go to the consulate of Panama, or Cambodia, or the Bahamas, obtain a similar certificate under another name, and continue the dance.

Toward the end of my stay in Singapore I visit the National Archives on Canning Row to satisfy a different curiosity. In 1897 Joseph Conrad signed on as first mate of the Vidar, a steam coaster owned by a Singaporean merchant named Al Joffree. He made five trips between Singapore, Sulawesi, and the east coast of Borneo. These trips, which included stopovers at river trading posts at Bulungan and Berau, provided the raw data for Almayer’s Folly, Lord Jim, and other works. It is also possible that the Vidar, and Conrad, engaged in another traditional activity of Europeans in the piracy zone: selling guns and ammunition to the locals in return for exotic produce. The plot of Almayer’s Folly pivots on the reluctant involvement of Almayer in a scheme to run guns to a part of Indonesia that was rebelling against the Dutch at the time. Netherlands colonial records from that period state; “the import of guns and powder by the Vidar was a matter of investigation.”

The Singapore harbor records for 1897-98 do not mention the Vidar at all, though she does show up in ship movement columns in the Straits Times. I learn later that in this city-state where newspapers and Internet messages can be censored for content detrimental to the well-being of Singapore; where jaywalking, leaving a toilet unflushed, or possession of chewing gum are crimes; that any historical records apt to embarrass not only Singapore but her Asian neighbors are locked in a separate section of the archives, for which special clearance is required. (fn)

I hook up with Rony and Amir and we hire a sampan to ferry us to Belakangpadang. The island’s main village is built on stilts over a bay opposite an island used for transshipping crude oil. Amin and I wait, as usual, in a kopitiam, smoking clove cigarettes, drinking sweet milky tea. Here, as elsewhere in the Riau archipelago, there is no shortage of young men hanging around as we do. Jahin, when he finally shows up, is not one of these; I noticed him earlier, a lean fellow in his late forties, strolling back and forth along the walks of this half-village half-deck, accompanied by youths wearing jewelry and long hair. Jahin has a cloth cap, a medallion, a ready chuckle. His eyes, like Abyankhar’s, stay on the horizon. He smokes a lot, and bursts some of the assumptions I made about attacking merchant ships. He does not, for example, use a rope and grappling hook, but rather a long piece of bamboo with a boxhook lashed to the end, to shinny up the sides of freighters. Once aboard, he will unroll one of the mooring lines and drop that to the sampan for easier access. And in coming up to the vessel he will bring his boat up the bubbles and whirls of the ship’s wake—then, leaping the first wave of wake, lay the sampan between the first and second swells, under the ship’s counter, as the pole-man fishes for purchase. However, Jahin adds, scanning the horizon, he is out of this line of work for good. The men in his village also have given it up for now, because of increased activity by local navies in this part of the strait.

Still, the syndicate is hiring, he continues; or at least, a man who he knows belongs to a syndicate offered Jahin a job two weeks ago for a hijack “sometime soon” in local waters. I press him for details. He chuckles. What he says meshes with what I know of the gang the Pulau Mas crewmember referred to. It is one of three cells that make up the group. Only one cell is used at a time. The immediate boss is an Indonesian who might or might not be “Mike,” from Wong’s old team. They hang in an apartment in Nagoya. They drink a lot. If I offer them enough whisky, Jahin adds, if I guarantee to make them famous without mentioning names, he might be able to broker a meeting. I offer whisky. Jahin says it will take at least a week to arrange. I’m supposed to go to the Philippines in two days but I repeat my offer: If this is for real, if I can really talk to these men, I will return to Batam.

That night, still on Batam, a South African who wears a kaffiyeh and claims he is a “legal consultant” takes me to a karaoke club. The Vovo is filled with Singaporean Chinese men looking smug and singing American pop and even sappier Chinese ballads to clusters of prostitutes hanging like September grapes on bars and couches. Anton introduces me to an Indonesian Chinese woman, with a classically lovely face, named Santi. As Anton warbles Rod Stewart Santi urges me to return later. She has a four-year-old daughter who lives with her grandmother in Jakarta and depends on the cash Santi earns at the Vovo. The going rate for a night with Santi is less than fifty bucks.

I don’t go back; but later that night I lie awake in my hotel room, which overlooks a shantytown full of hopeful and out of work Indonesians, and then the bay in which Pulau Mas is anchored, and Pantai Stress. The hotel is full of girls like Santi, and I think of her; think of the selat, too, and what it is in me that pushes me to court risk, however attenuated by probabilities or condoms, when if that risk were ever to achieve its potential the people it would hurt most would not be me, but those I love more than risk or writing. This hotel, or brothel, stands nextdoor to another karaoke, and all night the Singaporeans croon to their hired girls: It’s Now or Never, and I Can’t Stop Loving You, and the greatest hits of Tom Jones. And if I don’t go back to Santi it is mostly because of my family; but also it is in part out of distaste for this Third Millennium imperialism where the rich of the New Asia screw the poor of the old and sing, very badly, Delilah.

#

Three days later I leave for the selat.

The selat marks the end of the Sulu Islands, between the Sulu and Sulawesi Seas. The islands rest on a geological ridge known as the Sulu Tectonic Arc which includes a few volcanoes but is mostly made up of coral atolls accreted on the uplift. The volcanoes are dormant; what is not asleep in this area is a more human form of collision, for the Sulu Islands are Muslim and their inhabitants have been fighting the Catholic authorities in Manila since the Spanish got there in the 16th century. They kept fighting when the Americans arrived and then the Japanese and they are still at it. There is no air link to Tawi Tawi, the farthest major island in the chain, till the day I get to western Mindanao, which by bright coincidence is the day Asian Spirit Airlines inaugurates the first flight in over a year. Signs in Zamboanga City airport urge passengers to check in their guns. Soldiers and choppers patrol the perimeter. Military cops write down my name. Westerners are prime kidnapping targets of the local guerrillas, and the army wants to know who I was in case I disappear.

The plane, a molding ex-Chinese YS-11, flies down a line of plentiful clouds, and atolls whose lagoons are browned by mangrove, and reefs turning the water above them the kind of blue you see in cruise brochures. At one point an oil slick fans away from something sunken near a reef and I watch it as long as I can. This is, after all, the heartland of the Sulu sultanate, and the sultanate of Sulu, since the 1300s, was infamous as being the hot spot for piracy in the zone. Stamford Raffles, the East India Company bureaucrat who founded Singapore, wrote in 1811: “Sulu…has been subject to constant civil commotion, and the breaking down of government has covered the Sulu seas with fleets of formidable pirates.” More recently, Cockatoo, an online guide to the Philippines, posted the following newspaper account of the takeover by pirates of a Filipino passenger vessel crossing the selat: “Seven pirates armed with automatic weapons attacked the small boat with 33 passengers and crew…the pirates forced nine of the 16 males to one side of the boat and opened fire, killing them instantly.”

A sheer volcano, its top hidden by clouds, rises from Tawi Tawi’s eastern end, and a long lagoon cuts across its midriff. The shores are jungle, mostly, except for a beach road, a wide harbor. The road from the airport winds through jungle interspersed with palm-thatched shacks propped high on the usual stilts. Roadside stands sell gasoline and brake fluid in cola bottles to the jeepneys and sputtering tricycles that cruise endlessly back and forth. In Bongao port the stalls stand shoulder to shoulder and sell, in addition to fuel, miniature seagoing hearths, cassava cakes, machetes, and a brightly colored junk food named “Chippy Chips.” The bigger buildings are guarded by men with shotguns.

In a hotel on the northern shore I meet an ethnologist who works for the ministry of education. Talib Saugogot is a wiry fellow with a permanent grin that deepens, outlining harsh cheekbones and a total of two teeth in his lower jaw, when he talks about the folklore of the Sama and Tausug tribes who inhabit the Sulu Islands. Talib has been collecting these tales for years, and you could say his efforts are a form of family therapy, for Talib is half Tausug and half Sama and that is more complicated than it sounds. The Sama, who may be descendants of the first Austronesians to populate this area, are a laid-back people who until only a few years ago lived exclusively on their boats, fishing and trading and sailing. Whereas the Tausug, who created the Sulu sultanate and gave it backbone, are a people so tough and violent they make Sicilians look like a co-dependency counseling session. One might even term them bullying and vindictive, given their record, were it not for their habit of defying empires, and a concept of honor and friendship whose rigor calls to mind bushido. They also invented a system of mutual party-throwing, by which they resolve issues of wealth distribution, that I find attractive. The Tausug lived from trade and some farming but mostly from pirating and slave raiding. And as overlords of this area they evolved a feudal relationship with the Sama living on their graceful, claw-sailed lepas. In this relationship the Sama were serfs, providing the Tausug with the fruits of the Sundaic seas in exchange for protection and fair treatment. Because one thing about these “serfs” was, if things got too bad, the lepas would be gone tomorrow, so a Tausug overlord could not act too brutally without putting his private economy at risk.

But the picture contains scumbles and undertones, or so Talib implies, sitting in my hotel room by candlelight; the electricity on Tawi Tawi is provided by a power barge owned by the national utilities company and it works only half the time. New inputs fuzz the algorithm. One is agal-agal, the edible seaweed beloved of the Chinese and now cultivated on platforms on the coral in lagoons and offshore. Another is shabu, or methamphetamine hydrochloride—crank. It is smuggled in from Borneo and purchased with the proceeds from agal-agal. And of course guns remain a factor, and they too come in from Borneo, or are sold on the black market by Filipino soldiers, to add their quotient of instability to the mixture. Here is an example of how tricky it can get. Talib describes a recent incident where pirates attacked a boat full of fishermen. The pirates included several Sama, who ostensibly ran the craft. This reassured their prey who figured Sama were less likely to harbor ill intent. But when they got close, a core of heavily armed Tausug popped out of the bilges and did the actual gun-pointing and tough-talking.

More recently, a boatload of pirates working the selat between the island of Sitangkai and Sabah, in Borneo, were surprised by a Malaysian patrol craft and summarily machine-gunned to death. Only one man, who jumped overboard, escaped. That bunch was all Sama, Talib says, grinning less fulsomely, leaving me to work out the complexities by myself.

I will need to go to Sitangkai for this story, Talib adds, and I feel the nerves rev up, because that island is the jumping-off point for those wishing to cross the fifty-odd miles of open ocean to Borneo. Ferries are scheduled to leave on the overnight run from Bongao to Sitangkai tomorrow and the next day. Talib gives me a name to look up. He warns me not to cross the selat, because it is too risky, so of course the fear accelerates in me, because all along I felt it would come to this—that options would fail or erode, and I would be left with only the one choice: of putting myself in the heart of the piracy zone as prey.

I spend the next two days waiting for the boat, haunting the main wharf and also the Chinese Pier, where if I only knew it much smaller boats leave more frequently for Sibutu, from where I could hire a launch to motor me to Sitangkai. But no one at the roadside stands selling ferry tickets, or at the militia post by the harbor, clues me in. So I sit in black coffeeshops guzzling Royal orange pop while people gawk and call “Hey Joe! Where are you going, Joe? What is your purpose—Joe?”

I am Western enough to hate the waiting, and the loss of time, but at the same time—and I repeat the noun advisedly because the two forms of time are involved here—I enjoy hanging around the Chinese Pier. For this is the piracy zone Conrad knew. The prows of large wooden seagoing vessels, halfway between junks and caiques, line up overhanging the wharf’s capstones. Across the pier the godowns stand; they are small warehouses, unlit save by pressure lamps or the odd working bulb; piled high with copra, dried fish, trepang (sea cucumber), shells, agal-agal, live lobster, bananas, and other products of Sulu. In this nothing has changed since the sultanate’s heyday, when British and American merchants, desperate to find goods they could sell to the Chinese in exchange for tea—the Chinese being unimpressed with Western gadgets—came to Sulu; for China coveted the products of the Sundaic seas. The sultanate, for its part, lusted greatly for one product Western civilization has always made a lot of, namely guns. The Tausug needed guns not only to maintain their own feud-based culture, but to extend their reach across the strait to Borneo, and sections of Sulawesi and Mindanao as well. In the 1820s and ‘30s ships from Salem, Massachusetts, routinely ferried guns and powder from the U.S., bartered them in Sulu for local produce, and shipped that to Canton, where they loaded tea. And just as the godowns of Bongao’s Chinese Pier still sell trepang and dried fish to Guangzhou and Taipei, so arms remain a prized commodity here. The Philippines army complains that the Moro National Liberation Front gets regular deliveries of weapons from across the strait. Washington, of course, equips the Filipino armed forces to the tune of just under $80 million annually. And Gerard Rixhon, an anthropologist at Manila’s Ateneo University, says that when he ran a school on Sibutu, CIA pilots smuggling guns to Muslim rebels in Sulawesi regularly used his island as a refueling point, for Washington then considered Sukharno’s government a leftist threat. Sitting in the coffee joints, watching sweat-slick stevedores hump gunnysacks of rice or copra up steep planks from bow to pier, it’s easy to imagine that time in the Sulus is a commodity that shrinks and expands, folds in on itself and is cut crosswise so that you can never be sure where in the line of serial events you stand, or what strand of it, a day or a century old, might be coiling around your feet to trip you up.

To slice up the waiting I track down Adjarail Hapas at the branch of Mindanao State University in Sanga Sanga, at the other end of the lagoon. I drop in on him out of Western time, unannounced and demanding of information, and like most Filipinos he is far too polite to let his own requirements interfere with my desire for information. Hapas’ office looks out on Bongao Peak, populated by monkeys and Sama ancestors who live in a shrine up top. He shows me articles he has written for scholarly publications on leaders of Tausug resistance: Khamleen, who fought the Filipino army to a standstill in the 1950s; and Panglima Hassan, who battled the American army in the earliest years of this century. The Americans were led on occasion by Captain John Pershing, was to distinguish himself later on a more Hollywood scale of slaughter in France. The Kota Wars, as they were called, ended after U.S. troops slaughtered several hundred poorly armed Tausug on a hill called Bud Dajo. Hapas is slender and languid. He has a thin mustache and a sorrowful expression. He reminds me that piracy is in the eyes of the beholder, in the sense that what a Westerner terms piracy might in local eyes variously be seen as the seagoing application of political pressure against a rival sultanate, or resisting restraint of trade, or enforcement of customs regulations, or guerrilla warfare against a colonizing power. Certainly the history of the Malay archipelago is crammed with examples of all these piracies. Though there were and are pirates who operate strictly for personal gain, much of what the British termed piracy was really a kind of waterfront maquis protesting the European practice of reserving trade for the “stapled” ports of Malacca and Penang, or the Dutch exclusionary zone of Batavia. Sometimes it was waterborne raiding carried out by one river chieftain that the Europeans didn’t recognize against shipping owned by a rival. The zone is the piracy zone because of geographical factors, but political conditions exist that are a function of its peculiar geographical character, and these can be grossly summarized as the conditions of a saltwater frontier: large tracts of wilderness, both aquatic and terrestrial, that were tough for a central authority to control, and where chieftains straddling the land-sea interface could act pretty much as they pleased. In this environment, piracy and smuggling, slave-raiding and kidnapping, religion and import duties, resistance and outlawry were mixed so thoroughly that it was often impossible to sift out the different flavors or define them independently. And so it was easy and convenient for bureaucrats in London or Amsterdam to label all varieties of maritime violence in that part of the world “piracy,” and send gunboats to stamp it out.

Over the brow of coconut palms surrounding the college at Sanga Sanga, on a beach were Sama have erected a slum of stilted shacks, a sixty-foot kumpit is being built by a Sama artisan. It is a lovely hull, the kind of high-prowed cargo boat that crowds the wharves in Bongao, every line perfect. It is carved partly from huge trunks of trees that constantly drift over from the fragile forests of Sabah; kapor for the planks, lawohan for the strakes. The boatwright is a Sama de Laut, a Sama “of the ocean,” as opposed to a Sama de Lea, which is the term used for those who long ago gave up their boats to live on land. With no blueprints or sketches to guide him he crafts the hull from a template in his head, using three tools only: an adze, a knife, and a chainsaw.

The owner is a Sama de Lea, a former teacher. He will use the kumpit to smuggle cargo across the strait, and in so doing he may well become a victim of the pirates who lurk between this area and Borneo. Yet something about the owner’s quiet assurance, and the almost religious focus of the boatbuilder, remind me that not all Sama are cast in the turn-the-other-cheek mold; that quite a few were hired by Sulu sultans to raid for them on account; and that some sub-groups of the Sama, like the Lanun or the Balangingi, became professional pirates in their own right, feared on a par with Tausug raiders and the Bugis of Sulawesi and the Wako of Formosa. Legend has it that the first professional pirate was Lee Ma Ho, a Chinese; and the first people who worked for her were Sama, who later gave the Tausug lessons in how to catch and rob ships. I remember, too, the second term for pirate in Bahasa: badjau laut, or sea gypsies. It is the term Filipinos use to refer to the Sama.

#

The boat to Sitangkai is announced for eight a.m., then noon, then three. She finally shows up, a black shape outlined by running lights, at eight p.m: bigger than I expected and really rough, a former Japanese deep-sea trawler of one cargo level and two passenger decks entirely covered with rough cots except for a couple of passageways just wide enough to walk along crabwise. The wharf is full, so she docks alongside a coaster, and there follows a scene that terrifies me but that fazes nobody else, as every one of her two-to-three hundred passengers stampedes toward shore, tilting the ferry to starboard, and starts scrambling across the three-foot gap between ship and freighter. Women lean precariously across the dark water; hands grope in the histrionic illumination of decklights; grandfathers, cripples, swaddled infants are suspended between two huge steel hulls that would inevitably crush them to death if they were to slip; others reach out to grasp proffered babies, lift them to safety. Amid the thrum of diesels and the stink of exhaust, harbor water, dried fish and humanity, this appears to me a scene of shipwreck, like the chapter in Lord Jim where the young mate panics in a storm and abandons his cargo of terrified pilgrims. The more I see of these waters, the more I am struck by how closely Conrad modeled his fiction on scenes he witnessed. Now I wonder whether his novels were not largely fact. Two days ago—by way of example—I mentioned Mrs. Almayer to Jerry Hapas. She was the daughter of a Sulu pirate “chieftain,” and she turned against the white man who raised her, and the Dutchman she married, and embraced the culture of the trading port she lived in: either Berau, or Bulungan, in eastern Borneo (fn). I told Jerry it seemed unlikely to me that the daughter of a Tausug chief should feel sympathy with the half-Bugi, half Malay inhabitants of that town, when the Tausug were more used to raiding such places for loot and slaves. And Jerry said, “She might feel they were beneath her. But she could also feel a religious solidarity because Bugis and Malays are also Muslim.” And he reminded me again that it was possible Mrs. Almayer might be, not a Tausug, but a Sama, who would not feel the same contempt for potential victims.

The ferry does not leave at once. She unloads soft drinks and loads ton upon ton of ice, in blocks that melt on the quayside and are pushed through the pond of their own dissolution down a metal slide to the vessel’s gut. The Sampaguita Grandeur also carries on her cargo deck a load of stacked bamboo, both split and whole. But her perennial cargo is people. People of all shapes and ages. People both frightening by their numbers, by the sheer imposition they make on deck-space; and pathetic by their vulnerability, by that need for breastmilk or orange pop or a soft place to rest. The passenger decks are covered, literally and to a depth of two inches, with garbage. The open after section, by the twin funnels, is where people go, bearing a saucer of water for ablutions, to shit.

At four a.m. the loading and unloading are done. The ship leaves the quay without a change in the note of her engine. I lie on my cot, feet stubbed on one passenger astern of me, shoulder rubbing someone beside, jostled by those on their way to and from the after deck, realizing for the first time that I am riding a journalistic cliche, something condemned to be filler on page eight of the daily back home: an overloaded and superannuated Filipino ferryboat whose casualty list, should a fire start or we hit a reef or be capsized in a squall, would inevitably and despite the presence of lifejackets run well over one hundred. But the sea is calm and still, the visibility perfect under a yellow half-moon. An ancestor shrine smokes peacefully on the after bulkhead of the wheelhouse. At an open window the Chinoy skipper squints impassive down the trail of moonlight as his dog yaps around the feet of the crew and the prostitutes who service the Grandeur’s officers yawn, and put on makeup, and crack jokes about the sleepless Milikan.

#

No movie scout would choose Sitangkai as a location. It comes out of the sea like an apology for the intrusion, a thickening of water in the shadow of clouds, more and more fishing shanties perched on stilts balanced on coral reefs; mangrove-rimmed shores framing a shallow lagoon many miles in diameter. The ferry docks at the lagoon’s nearest end, at a pier poured on an excrescence of coral and otherwise covered with godowns and shacks and surrounded by docks and arrangements of catwalks and shanties. The way into town is a parade of small launches that race each other through the coral down channels so narrow the boatmen have to fend each other off with bargepoles in passing. The anthropologist in Manila told me with a noncommital smile that Sitangkai was nicknamed “the Venice of the South,” and having been to other “Venices” in my life—in London and southwest France and California; any place with more than three canals within a square-mile area seems to earn the epithet—I anticipated little resemblance. And yet, wedged in the bombot’s bilge as we steer through the suburbs of stilted cabins and enter a wide canal, I realize this place really does look like the real Venice. It’s not as grand or big of course, it’s more of a clamshack Venice, or perhaps what the city on the Adriatic looked like early on, when it first served as a refuge from Wisigoths. The waterway is lined with market stalls and a few taller, balconied buildings, and at intervals side-canals open into darker and more complex windings, and the mud stinks and the water seems to lie thick with plots and ink. Bridges exactly like the Italian version, with steps on each side and a high arch in the middle to let boats pass, cross the waterways at frequent intervals. A couple of them bear structures resembling the Rialto’s. And the boatmen cut their outboards and call to each other and pick up poles to push their craft, which are thin as gondolas and black in the uncouth equatorial morning. Disembarking, the launch’s mate leads me across a series of boardwalks and bridges lining a dozen side-canals, where everything, walkways, shacks, shops, shanties, is built on thousands upon thousands of thin poles standing on the abused reef and the merciful swirl of tide. Talib has a friend back here; he is the principal of the Panglima Alari Elementary School and a significant figure in the Sama community. His house is bigger than most, and Hadji Musa Malabong rents the upstairs room to strangers. For besides having no electricity (except for personal generators), telephone (outside of the lone “telephone office” in town), running water, or sewers (if you discount the tide), Sitangkai also possesses no hotels.

It’s at Hadji Musa’s that I meet Lanne, who will introduce me to the people I need to talk to; who, it seems possible, will take me to the selat; who will also acquaint me with those still practicing the trade of piracy. Lanne is long-faced, and tall for a Sama. He has a small administrative post in the local barangay, or ward. He knows many people on the island. Lanne is fiercely proud of his own culture, and collects Sama folktales. That’s how he knows Talib, and it’s because of this angle that he wants to help me; anyone interested in the Sama, even from the piracy perspective, interests him. Lanne is also volatile; when I first tell him what I want, he gets excited and starts rattling off incidents, and people he knows who know people and so on. Then, only a few minutes later, he appears to collapse into depression, and silently stares off across the canal by Musa’s house, and I wonder if I said something wrong, or if he is seeing the other side of this project—that it could reflect badly on Sitangkai or the Sama, or get him into trouble, or worse.

I spend a lot of time staring into space at Musa’s while Lanne is off seeing people and, I hope, scoring contacts for the Milikan. I got used to waiting in Batam so I can hang out a little easier now. In any case it is pleasant to wait here. My room has louvered windows on all four sides. Two face the web of corrugated tin and palm-frond roofs, the wooden decks and toxic water of town; another looks across further canals to the minaret of the nearest mosque, where Musa’s nephew is the imam. To the north, the canal on which we live cuts through the town’s other side to a few agal-agal shacks, and then the long, smoky blue expanse of the selat, the horizon always besieged by brigades of equatorial clouds marching south. During the day it is very hot, but a breeze usually runs through here as casually as the crowds of children who scamper in and out in pursuit of kids’ most solemn objectives, shaking the house on its frail structure as they go. The family on the dock to the north builds boats, as the man in Sanga Sanga did, direct from brain to hand to wood. The docks to the east and west belong to fishing families and they live on those patchwork lanais, flaking out their catch of fish or seaweed, repairing nets. When daylight fades they stay outside till late, eating, chasing kids. Before dawn Musa’s nephew cranks up his tune of minor keys and grace notes to praise Allah for the almost invisible pearling of gray to the east. And then the fishing families conjure fire from their lapohans, the bidet-shaped clay hearths that Sama have used to cook on boats from way before anyone can remember, and from then till the following midnight the air is perfumed with the smoke of junglewood and frying fish and steam from rice, which is the staple of our diet here. Through the barred louvers I watch them like a spy, the families who squat by woks, eating with their fingers. I learn to recognize whose kids are whose, and which parents take boats out fishing. I know the women suckling, and a grandfather who wanders with an infant ever in his arms. This part of town is peopled entirely by Sama de laut. They were the untouchables of the Sulu Sea, lowest in caste, despised by the Tausug for not being “real” muslims, though their version of the faith was similar. Musa, who was born and raised on a boat and as a child sailed with his family down ancient trading routes to southern Borneo, has set up a group dedicated to preserving the culture of the Sama de laut before it is eroded by landbound ways and crank and the corruption of the Filipino body politic. He imagines building a big lepa and using it as a classroom to teach old skills, like boatbuilding and trepang fishing. “The Tausug want boats; we can build them boats. Why not?” Musa says. But the Tausug are also a problem. “Twenty years ago,” Musa says, sweeping his hand to take in all of Sitangkai, “this place was all Sama. Now there is over fifty percent Tausug in this town. On this island, maybe twenty percent Tausug.” They are driven here, he adds, by the guerrilla war flaring in Jolo and the central islands of the chain. Sitangkai’s mayor and the congressman are both Tausug. When I talk to him later, Lanne confirms that many of the local pirates are also Tausug, and if you visualize the Tausug as an organized platoon, which in some ways is not unfair, then the pirates function as point, taking the first ditches, attacking Sama boats, stealing their equipment, threatening those who don’t leave their seaweed farms when informed, firmly, that these stand in waters now controlled by Tausug.

I meet the mayor early on. Musa’s son guides me to a coffee shop full of shadows and deep booths, and men with guns who hang around looking tough. We are stopped three times on our way through the back, but when I finally meet hizzoner he declines to speak on grounds that his English is not good, though it seems serviceable to me. Later that day I take a bomboat back to the ferryboat island to meet a friend of Hapas’, a cigarette smuggler. “Pirates,” the smuggler shouts; it’s the conversational equivalent of a wrestler grabbing hold of his opponent’s belt. We are sitting in another coffeehouse, crowded with men waiting to board one of the Sampaguita company tubs back to Tawi Tawi, a process that will take time, for two hundred tons of agal-agal in gunny sacks await loading and only a half dozen stevedores can do the job, balancing on their shoulders sacks that are the size and weight of the dockers themselves as they tread twin planks to the cargo deck. “All crimes in the Philippines,” the smuggler says, “can be traced to politics. Politics here is a business investment. You get office, you cash in—the people suffer economically and they are forced into a life of piracy.” In Sitangkai, he adds, politicos employ pirates, not directly to steal boats but to draw on their stock-in-trade of violence when enforcers are needed. “The Three Gs of politics,” the smuggler declaims, even louder, and pounds on the table, causing his companions, who have heard all this before, to laugh uncertainly. “Guns, goons, and gold. You need them to get elected—and once you are in power, you can never resign. The pirates won’t let you.”

The smuggler is a Tausug. He treats me to soda. He tells me that most of the pirates, though by no means all, are Tausug. They are violent and dangerous, but that, he repeats, is the fault of politics.

For several days I make more progress on crossing the selat than I want to at this point. It is Musa who indirectly makes the connection, though he wants no part of it really, because the trip is risky due to pirates and the intrinsic hazards of crossing fifty miles of sea at night in an open boat. It is also illegal, since the Malaysians don’t allow “backdoor” entry. Still, a friend knows a friend and the second friend brings his boat around to show me how strong and fast it is, and in truth it is a good craft, a “speedbot” maybe fifteen feet long, lean and tightly built and powered by a fifty horse Yamaha. He can pick me up in four days, the snakehead offers, and take me to Semporna, which is the nearest town in northeastern Borneo. And I agree, feeling nervous and also excited because at thirty knots this boat could be across the selat in an hour and a half. And Semporna is only 150 miles from Bulungan, which was Conrad’s last port of call outbound on the Vidar.

From the telephone office, I call Rony in Batam. He tells me that Jahin’s pirates have refused to be interviewed.

I push Lanne harder. I may have seen a pirate by this time—a fellow who Musa says works in a pirate crew, who lives in a nearby shack, but has no interest in talking to me. I have met victims, too. Musa’s cousin was recently chased in his fishing boat by a boatful of Tausugs in a fast launch. He lost his engine, his fuel tank, his Briggs and Stratton controls. It was a seaborne mugging, a treble note on the scale of violence that sounds like plain chant across this lagoon.

Musa tells me the story of the sergeant fish, a creature with a snout that looks like it was pounded flat by a hammer. According to the Sama, the sergeant fish once had an elegant nose, until the day the Bamban fish snuck up behind him and screamed, “Look out, pirates!” This panicked the sergeant fish so much he swam into a rock and crushed his face.

I don’t sleep well. I have come close several times to finding what I came for only to be stymied at the last minute. I’m growing a little paranoid, frankly; as if the piracy zone were a vast conspiracy designed to lead me on and on and disappoint me at the end with fables. In my urgency I use cliches, patronizing neo-Asian allegories, on Lanne. “It’s like I’m hunting tiger in the jungle,” I insist. “Everywhere I go I see bones, I see paw prints. I hear stories about what he’s done. Sometimes I catch a flash of movement, deep in the trees. But I never see the tiger. And now I wonder if he really exists.” Lanne, who wants me to sponsor him for a visit to the States, squeezes his contacts, or pretends to. Maybe he’s just playing me a little to see what else I will offer. At any rate, shortly after my tiger speech, he remembers a pal of his who works odd carpentry jobs with a pirate. The trick with this particular tiger, Lanne says, smiling sadly as he reprises my analogy, will be getting him to open his mouth. “He is a real pirate, this man,” Lanne continues, staring moodily across the dock. “He has killed many people. He has a scar in his face from a bullet,” and Lanne points to his own cheek, “from a machine gun.” None of this seems to make Lanne happy.