This is the original version of an article published in Harper's Magazine, in much shorter form, in late 2008. What I wished to do in this piece was view what's going on in India through the prism of its film industry, while fully accepting the bias inherent in being a "Gora"--a white foreigner in Bollywood. See what you think ...

The causeway leading to the shrine of Haji Ali stands six feet above the filthy surface of the Arabian Sea when the tide is low, and several feet underwater at the flood; but during the eight or nine hours when the half mile of paved jetty lies above water it is covered with pilgrims walking, limping, crawling to and from the bright white temple housing the saint's tomb at the end. There are always crowds of pilgrims, and many live off them—for the saint, who drowned in a shipwreck on his way back from Mecca, and whose body somehow washed ashore here, in Mumbai, his hometown, is said to hold power to grant wishes and heal the ill; and the sick and crippled, not to mention the vastly poor who come to touch Ali's tomb in hopes he will work his magic, are primed to make donations to help things along and that manna sometimes rubs off on causeway beggars.

I weave through thickets of hands rising from families camped in pools on filthy pavement. Blind men walk with one palm on the shoulder of guiding boys. Circles of bodies, skin turned obsidian by the sun—bodies lacking arms, legs, thighs—lie with nubs of arm resting, for companionship or just to maintain the comfort of that circle, on the stubbed thigh of the next body over; waving their free stumps as they repeat "y’Allah" in endless call and response. Just before the steps leading to the shrine rises a series of stalls. Among the stuff for sale, plastic sandals, pictures of the temple, are t-shirts showing the faces of Salman Khan, Shah Ruk Khan and Amitabh Bachchan, bright stars of the Hindi film industry known as Bollywood; no, more than an industry, a shining city of white and hope like Haji Ali that whose princes attract even those come to this place with less than nothing to lose.

Inside the shrine an imam circles, orchestrating donations from those clustering around the sarcophagus, and I stand back, reluctant to disturb the force of their hope—not loath, however, to make a wish, that I get what I came to Mumbai for: a part in a Bollywood flick; some role as outsider—at six-foot-two with green eyes I cannot pass as Indian—that will allow me to see from within how Bollywood works; how India works, perhaps, in defining who is accepted and who rejected by this culture that has been slaughtering, assimilating, adapting to outsiders for ten-thousand years. I will likely need the help of saints to plug into this arc spun between misery and shining excess, between the temples of cinema fantasy and the jury-built squatters’ shacks that are home to half the population of Mumbai, or Bombay—and there’s a story behind these binary names, as there seems to be a story behind every facet of this city and the films that represent it.

Back along the causeway, as the touts of the Haji Ali Juice Center sell persimmon liquor and lhassi, amid the swirl of cars and fumes and honks a black-yellow taxi swerves to pick me up. The white man sitting in the rearseat gloom is Tom Alter. This is the master; dean of gora actors, of Westerners in Indian cinema. Alter is tall and thin. He has a white beard, eyes blue as snowmelt, an uncompromising North European nose—Donald Sutherland, perhaps, crossed with a retired Erik the Red. When I talked with him by phone from the U .S. the first thing Alter said was, “You have to understand, I am not Western, I am Indian.” This is true in all important ways—he was born to an American missionary family, grew up in the Himalayas, has spent his life here. He speaks better Urdu than most Indians. His English, while perfect, is Hindi-flavored, and reminds me of call-centers and bills unpaid. Yet Alter cannot look Indian without makeup and therefore he has spent much of his career playing characters he is ethnically identified with yet also distanced from, by virtue of prime belonging. “The most obvious component of Western roles,” he tells me as we ride, “is the British. There were a lot of films made where the British were identified as real villains.” Alter has acted in over 250 films. He has played Interpol cops and Western Mafiosi, a drug kingpin’s chopper pilot, sadistic officers of the Raj. Lately the roles have grown more nuanced, more positive. In Mongal Pandey he played a British officer who befriended an Indian rebel. That relationship was so complex, he says, that audiences were not ready for it; but attitudes are still changing. This, I soon learn, is the party line for many Bollywooders. In part because of colonial history Westerners traditionally have been cast as heavies, brutes, the bad guy—there was an Aussie actor in 70s Mumbai, Bob Christo, who was known solely for beating the crap out of people on celluloid—but as India morphs, becomes a power in the world, Western roles in Bollywood are adapting too, allowing for the kind of complex, equal alliances that Indians also seek in commerce and global politics.

The taxi stops in Bandra, at the Taj Land’s End, near the downtown end of the northern districts; the northern districts are where Bollywooders tend to cruise and work. The Land’s End is a hotel in the Xanadu style, owned by the Tatas, a family of Parsis. Parsis, and their slapstick dramas, were an important feature of early Indian films; the Tata Group owns a studio in Mumbai. Alter is MC-ing a press stunt for a DeBeers marketing conceit at which the top attraction will be Amitabh Bachchan, aka the “Big B,” one of the stars I just spotted on a t-shirt at Haji Ali. Amid the spotlit opulence, the forty-yard-long buffet, the stacked bottles of Moet, the freeloading PR critters, Alter delivers his spiel like the pro he is, intoning the adspeak as if it were Shakespeare: “One tiny look can promise so much; one little gesture can mean the world…” Then Bachchan shows and, in terms of press-suction, it’s as if the black hole of Cygnus X1 had yawned open next to a laboring dustbuster. He is mobbed. Reporters and photographers scale each other’s backs to see him, it reminds me of blue crabs in mating season, each carapace mounting its neighbor’s; it takes ten bodyguards to hold them off. Over the walls surrounding the Taj compound dark heads, from the crowds always walking, walking around this city, peek and call to Bachchan, who takes no notice. Between us and the sea rises another giant hotel, the Sea Rock, empty and dark, its revolving restaurant frozen since it was bombed by Islamic radicals in 1993. On our way back we skirt Mahim Junction railroad station where more bombs killed 200 people on suburban trains last summer. Our black-and-yellow taxi whines and honks, ornery wasp in a nest the size of LA; strung and trapped in the knots and lines of smoke and mad-dog speed that tangle together everything on these blasted roads: trucks, bullock carts, taxis, sacred cows, beggars, people walking, sleeping on the pavement—I have not been here so long but already I feel tied into this exploded churn, this feel of no-limits in volume and blasts avoided or not; the feeling too that C4 and utter traffic notwithstanding, this city somehow manages to go on via a surgical removal of angst—let bombs explode, let another ten thousand families crowd weekly into Dharevi, Asia’s biggest shantytown, right beside Mahim—Mumbaikars won’t notice particularly or care.

My friend Anil works at the Bombay Times, the prime scandal sheet for Bollywood, like National Enquirer and Variety rolled into one—so powerful that a mention in its pages, for a struggling starlet, an actor clawing for a part, can mean the difference between fame and failure. The “Boomtown Rap” feature is so influential that the Jain family, which owns Times of India, which owns the BT, openly flogs “news” items in “Boomtown Rap” through its Medianet service: 50,000 rupees for two lines with your name and what you were wearing at Nihal’s party. Anil is a party-beat writer (he has since left in protest at the paper’s retail theory of journalism); he has been my cheerleader and contact with Madhur Bhandarkar, one of the “new” Bollywoodians. This is a group of youngish directors who have started breaking away from the standard masala, the spiced-up— (masala means “spice stew”)— chopped up, throw-everything-in-and-if-there’s-a-problem-toss-in-more, tradition of Hindi cinema—a very Mumbai recipe, come to think of it, though films in this style are also made in Bengal, Chennai, Tamil Nadu. The churn of cars, religions, saints, migrants, ancient customs and new corruptions multiplied to the edge and then blown through whatever bulkhead defined the edge—masala is an extrusion of Bombay, only with music and dancing girls. Anyway these filmmakers have started tackling themes that take them further afield than the usual Bollywood plot about gorgeous daughter forcibly betrothed by wealthy family to rich boy but she falls in love instead with handsome not-rich boy nextdoor who must save girl from monsoon floods/kidnapping/fate worse than death to earn her hand.

Bhandarkar’s last flick, Corporate, featured a Westerner in a minor role. He is about release another film and is set to shoot a third, titled Fashion. He has promised me—long distance, by telephone, through Anil—I mean I know this is a promise, we’ve gone over this often enough, dammit!—a role in Fashion, which naturally must include languid tall middle-aged green-eyed Western men come to outsource cocktail dresses and hiphop hoodies to cut-rate South Asian apparel plants: the modern equivalent of Bombay’s huge cotton mills, which now—their product itself outsourced to cheaper regions—are being razed by Bombay city government to make, not flats for the city’s six million squatters as the law stipulated, but flash boutiques and apartment towers for those who can afford to pay legislators to flout the law; those same educated, forward-looking, English-friendly élites who, presumably, pay to see Bhandarkar’s films.

We call Madhur on Anil’s cell. I’ve had trouble getting through before but this time we connect at once. “Yes,” Madhur assures me, “we will definitely get together.” “I wanna talk about the role,” I whine, “I’ve been thinking”—and I have, I’ve worked myself into a real character here, one of those thin well-groomed types at ease in both Hyatts and Haitian sweatshops; conscious, perhaps, of “fair trade” ideals but fundamentally cold to anyone who doesn’t dress like Vogue before Vogue focus-groups the spread— “Yes,” Madhur says impatiently, the line is going bad, “yes call me tomorrow, goodbye.” Boom. “He is very busy,” Anil says soothingly, “don’t worry, he’ll come through.”

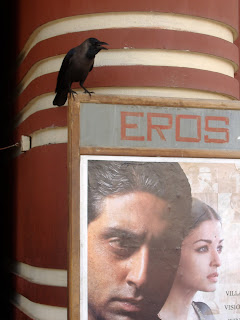

That evening, back in my hotel—it’s a pea-colored pair of concrete cubes near the seafront on Marine Drive—I sink into a Long Night of the Out-of-Work Actor; sweating in the gloom, the pissant airco. It’s all too hard, I think, I’m wasting time and cash on a narcissistic snark-chase, betting it all on a Kool-Whip promise from a busy director. This is typical, I rage at myself, of the dreamer-dilettante style of thought that has kept me from earning the hedge-fund-manager wages my ego clearly entitles me to. I find out later that this hotel, this very floor, have earned their bad vibes: here was where the team of Hindu extremists hung before traveling to New Delhi to off Mahatma Ghandi. The next day I move to another hotel; this one is a Twenties mansion of rotting stucco, balconies, ceiling fans, all leaning on banyan trees and pink-flowered vines. Crows caw in the branches, cats and rats amble together in the courtyard … More to the point it’s in Colaba, and on the Causeway nearby stalk the touts who prey on tourists—my Plan B.

I’ve been talking by phone to Darwesh, who hangs out next to the Regal Cinema at the northern end of Colaba Causeway and makes a living finding Westerners when the studios want goras for a shoot. By all accounts Darwesh and his ilk have plenty of work because the studios, almost all up north—Bandra, Andheri, Goregaon, Film City—routinely need a white face or ten to use as bling in bar scenes, or any shot where it’s important to look rich, cosmopolitan, jetset. It seems Darwesh is in Goa now but he hooks me up with his associate, Jesse. Jesse, when I finally reach his cell, sounds young, American, and mightily hung over. He is too tired to see me now or tomorrow, he says, but there’s always work; he’ll let me know if he isn’t in Goa. Another contact I have, Warren, tells me to call “Tiran.” He, Warren, is in Goa also. What is it with Goa, I wonder. It’s the beach resort where the young and fair whom studios want for that Western look flock when they come to India; but it’s a full night by bus from Mumbai, and everyone tells me Colaba is, no fooling, where touts find extras. Most of the touts call themselves “coordinators,” though they chiefly work for a slightly higher life-form that freelances for casting agents or studios; their headquarters is Leopold’s Café, on the Causeway, an old Parsi joint that ordinarily would be dark and full of old men smoking and drinking chai as in Mohamad’s across the street, except that the owners have tarted it up with posters of Elvis and James Dean, with waiters in uniform and hamburgers on the menu to attract foreigners who are often wary of dark smoky places with old men drinking chai. Outside Leopold’s a dark-skinned man with a bhindi dot on his forehead and a California accent clear as rain in Mammoth tries to suck a nubile Aussie into a tour of “Bollywood studios.” I ask him if he finds work for extras. “Yeah that’s what I do, man, for 2,000 rupees, I mean I’m an actor too, I’ve worked in L.A. but I’ll be upfront with you it’s a business for me.”

I buy Raja a beer. I’ll pay him an agent’s fee if he gets me work. Raja has killer’s eyes. He reminds me of a guy in Casablanca who sold me “best quality” hash that turned out to be henna. But Raja introduces me to Imam. Imam is a genuinely well-connected agent/dancer/actor/choreographer and yoga adept (“your broadness is huge,” Raja gushes to him when we all meet). Leopold’s depresses me, the fakeness of it turns me off. What I’m starting to like about Mumbai is how normally it’s hard on such hype. Hype exists of course, it’s a unit of currency in Bollywood, the Bombay Times sells it retail. At the same time this city seems too extreme, by all measures—too gigantic, too fast, too non-stop, too hypercharged with in-your-face awareness death people hope—for hype, which is thinned by hard facts, to build mass. I have seen a Lamborghini park next to a Dunkin Donuts in the fanciest street in town, beside a sacred cow, beside a family, with babies, cooking chilis on the sidewalk. Squatters live, sleep, fuck on the dirt road in back of the best buildings in the ritziest neighborhoods; every Park Place has its shantytown. Stars quaff Moet and look elsewhere but everyone knows damn well that every night, half the city; six million people; shits in the gutters. You can only fool yourself for so long in Mumbai.

At the same time this aura of blowout, of connections loose or exploded, of triple-dose quiddity and speed, allows people like me to exist: people who arrive here expecting to become an actor within three weeks—because everybody I talk to, directors, film journalists, actors, touts, assures me that will happen. “Anything can happen here,” Brandon Hill tells me; he’s a New York comedian who after only a few months in Mumbai scored a role as the gullible American billionaire who gets conned by Amitabh Bachchan’s son, Abhishek, into buying the Taj Mahal in Bunti aur Bubli. “This is not Hollywood,” says Gary Richardson, an American actor who has lived in India seven years. “Over there everything is structured, you have to be union. Here everything is fluid. Next month you really could be a star.” I figure in part it’s the deep hospitality of Indian culture that wants to stroke visitors by making their wishes come true; Hinduism posits that every guest may be a Shiva in disguise; but on another level it has to do with the size and the rough-and-ready nature of Bollywood. There are more jobs, more films—between 600 and 1000 flicks per year, nobody knows exactly, over half shot in Mumbai. It’s a planet of indies. How such vast roughness might work in favor of Dimesh, a 16-year-old who ran away from a drunken father in Jaipur to live in one of the zopadpatties, the urban shantytowns, and hawk plasticized maps of India to the tourists on Colaba Causeway, I have no idea. “That is my dream,” he says, standing outside Leopold’s, jostled by the other hawkers flogging brass telescopes, t-shirts, plastic figurines of Ganesh and Shiva. “I can be an actor.” I call Madhur almost daily and get only his answering machine. The touts are hopeful; there’s a shoot coming up at the airport, Kiran tells me, I’ll be able to work on that; but so far nothing solid. I walk late at night, near the dhobi ghat, the open-air laundry basins; the western shantytowns. I’ve started seeking out mini-temples, the homemade shrines people in the zopadpatties put up—to Shiva and Vishnu, of course, but more often to Ganesh, the elephant god, avatar of Shiva, known as a good-time dude. I look for altars to the gods of Bollywood; Bachchan has a temple dedicated to him in Tamil Nadu; but find none. By far the greatest number of shrines are dedicated to Sai Baba, a saddhu, or saint, who lived 150 years ago in Sirthi, in nearby Maharashtra province; he was famed for preaching tolerance and mashing together Hindu and Muslim rituals. Sai Baba seems a good saint to invoke now, since important local elections are scheduled and the Shiv Sena, a Hindu nationalist party with loud support in Maharashtran slums, is making a lot of ruckus verbal and visual with their Mumbai-for-Hindus rhetoric and saffron colors—Bombay is called “Mumbai” now because of a Shiv Sena provincial government, that trashed the old Portuguese moniker—bom bai meant “good bay”— in favor of a name based on a local Maharathi goddess, Mumbadevi. It’s not because of ethnic unrest that I keep to lit streets, though; it’s because of Beerman, a serial killer who has so far knifed seven men in this area and on Marine Drive. I drink Jameson’s in my room, but sparingly, because the government has, in honor of the elections, scheduled five “dry” days when all bars will be closed. I must husband resources.

#

One day I take the local to the northern districts, where the studios live, to see Ketan Mehta. I take this train almost daily but it keeps surprising me—buff metal coaches big as a double-wide trailer stuffed with ceiling-fans and straps to hang on, into which at certain stops a thousand rugby teams of Indian men scrum aboard elbowing yanking shoving so hard that if you’re not one of the fortunate grapeclusters of humans gripping handholds through the open doors to hang outside the train in the stinking breeze or ride the roof, that too you end up having unnatural sex with several people at once—OK not sex it’s more like a new kind of yoga, you find your limbs and arms twisted against your will among the limbs of other men (women have their own car); you feel like Shiva on acid with eight arms that are both yours and others’ wound in kinky knots around your body: train sutra. Mahim, Vile Parle, Khar Road, Andheri, Jogeshwari. After the train it’s worse, to get anywhere you must hire a motorized rickshaw, a hellish motorbike with a seat and canopy tacked on that dives immediately into a maelstrom of exhaust, dust, and gridlocked rickshaws—every trip in this area requires 25 minutes of auto asphyxiation. Mehta is one of the new directors. He made The Rising with Toby Stephens as a Brit captain who, he says, is not a caricaturized villain but a man of real sensitivity. After leaving Mehta’s I call Madhur and again he answers first ring. “Who?” he replies, when I introduce myself. “Who?” When he figures it out he says we’ll meet tomorrow. Breakthrough! I must cash in on this streak of luck. Mehta mentioned a shoot going on in Film City right now with Shah Ruk Khan. It’s some kind of 70s spoof, he says, that is sure to need white faces. Film City is an industrial zone for movies, northeast of the northern districts, built inside a national park named for the assassinated son of the assassinated Indira Gandhi. As I ride the hellish rickshaw I notice the russet smog that hovers over Bombay like a guilty past lighten somewhat. A range of hills opens over the rotblocks, the slums. I talk my way past a guardhouse and through a gate and we start to climb into jungle up a grade so steep the rickshaw slows to a crawl and my driver gets out to push. This is a big park and it is ill advised to leave the studio to piss in the bushes because leopards live here and they have developed a taste for gaffer. And for villager. No area of Bombay is free of squatters and their shantytowns; shanty-villages in this case; occupy, here a hollow in the trees, there a hillside. Perhaps the cats hunt only by night because at all times the roads, the bush, shiver with lines of children, women, men, walking nowhere. Suddenly out of the dusty green scrub an incongruous scene emerges—a Greek temple towers cheek by jowl with a Rajput palace, a Mumbai high street. Between a hill and a lake so distant it looks like lowlying fog, Anghkor Wat. A studio, on top of a mountain, resembles a SPECTRE hideout—closed. SPECTRE is out of business, and Shah Ruk is MC-ing a television gameshow today; this isn’t unusual for Bollywood actors, who often work three productions at once. Anyway no one needs goras here. Try Studio 10.

Several soundstages are grouped in the valley and I dismiss my driver. Through one door a man and a woman gaze passionately at each other, their profiles hard as nacre in the kliegs. An actor I vaguely recognize tries to break through a cordon of meaty bouncers outside a building labeled “Municipal Court,” and is severely beaten for the camera. The director demands take after take. Rickshaws, trucks, women with packages on their heads, walk unconcernedly behind the fight scene. Continuity does not seem a big issue. I trek around a dusty hillock; under trees, growing fruit like hand grenades, on which monkeys chase each other and parrots flit… It feels good to be in the country, or at least in the not-city. The smell of woodsmoke, from cooking fires, that permeates every inch of Mumbai is still present, but up here it is not fouled with exhaust. Car horns buzz but faintly, from Goregaon. Two rows of what look like abandoned 747 hangars, khaki colored, stand to my right; a family cooks rice over a campfire to one side. I spot a girl in the doorway of an orange blockhouse between two of the abandoned hangars. She is blond and slim and whirls what looks like two boleros, dipping to their rhythm. I walk up to her. She is maybe 28, pretty as Christmas morning, with eyes the color of jade. “I am dancer,” she says, jerking a thumb toward the door. “They don’t ask me now because I have dreads.” Katya is a painter in silk, from St. Petersburg. The blockhaus is basecamp for a ten-“girl” dance troupe, all but one from Russia; all but Katya brought here under contract. A tall dude, also in dreadlocks, claps and yells: “Girls! Girls!” All walk to the next hangar, and I follow, uninvited. A black curtain at the entrance is pulled aside; darkness, cool air, seems to reach out for me; at last I am on a shoot.

And damn, it’s like a nightmare from my bad old days, when I’d drunk too much to think straight but not enough to go home, and ended up, horny, seeing double, chasing babe in joints like this: a crass disco rises from the darkened set. Black and red walls in Marimekko shapes, a raised and spotlit dance floor, posters for French movies, a cocktail bar on the right. Next to the bar, a bearded man in a black fedora sits at a table bearing a keylit chessboard, glowering at the stage. People everywhere, gaffers with their duct-tape chains, carpenters, lighting hobbits, assistant directors, camera crew, chai men; also a bunch of people hanging around with no obvious job, just watching as the girls are wrangled to the stage shedding t-shirts, revealing lace-up leotards that expose a max of fishbelly. “Music!” A thumping, Hindified disco starts to pulse. “Roll camera. One, two, three, and—action.” I’ve been on sets before but my pulse jacks up nonetheless—this stage-management of fantasy, this melding of sex, music and fine lighting, reminds me not only of the five-odd months I spent in drama school, and my odd stints as a bit-part player, but of the basic act of story-telling in which I, as a novelist, am daily engaged at home. The girls go through a routine, legs flashing like sabres, rumps thrusting arrogantly—they do something pretty with their hands, and freeze in place. The music stops. “Number ten,” the choreographer’s voice echoes over the PA, “you were slow. Do it over.” The dance-queen is thirty-ish, hard ass; her two assistants demo to the Russians micro-details of their pas de dix. They go through eight more takes. Spot-boys bring the girls Bisleri water. Russian dancers are treated well; they rank second in a four-layer system of which Anglo dancers are the cream. The third level consists of educated, bourgeois Indian girls, dancing for a lark or because they wish to break into film. The lowest in stature are the “junior artists:” pros, chorus-line dancers who do the real work. No one messes with the first three castes but the junior dancers work sweatshop hours for a pittance. They are often hit, coerced into sex, abused in myriad ways. Nobody complains. It’s a fact of life, just as it’s a fact of life that Russian mafia are in Goa now, running hookers; or that black money, mainly from Muslim mobs like the Dawoods, still funds a bunch of Hindi flicks. Banks lend more than formerly to studios, but the smaller films are still fine ways to launder cash. It’s just the way it is.

The afternoon wears on. Things break, lights are switched; for every change or repair a team of ten men is ready to haul kliegs, scale staging, drop to hands and knees to rag-buff the disco floor; fetch chai for the director, Priyadarshan, who sits aloof, smoking, watching a monitor. I am awed, despite this overstaffing, by the rough-and-ready efficiency of this operation. You won’t find Teamsters busting ass like this, no java-breaks no OSHA harnesses no doughnuts. I am even more struck by how everyone: upper-caste Punjabis, masked Jains, yarmulke-d Muslims, dalit “spot boys”—seems utterly dedicated to getting this fifteen-second take exactly right. Here’s the old-fashioned masala, I think, throwing in everything: New York disco, Moscow dancers, Hindi pop, Punjabi star, to craft something that will wow them in the mountains of Uttar Pradesh, in the slums of Kolkata, in the exile videotechs of North Jersey. I find myself wanting desperately to be part of this. He could be me, that sinister guy in the black fedora; I could play the Ukrainian pimp, the L.A. drug dealer, my pride threshold is low; I’d be the Western boyfriend of, say, Katya, hanging around the bar. I was a pro once, as a child actor I played Joseph in a network Christmas pageant, I did Pal Joey with Arlene Francis in summer stock for chrissake—OK I had no lines but Arlene herself—we’re talking about the star of What’s My Line here—told me how well I acted acute jealousy of Joey. I lounge at a table by the stage, ready for my close-up, frowning at fedora-dude; no one notices. Finally the star sashays onstage. Payal Rohatgi struts through her dance moves between two lines of fair Russkis to freeze as they do at the end. She says nothing to the dancers or anyone. Between takes her personal makeup artist applies gloss. Between takes I sidle up to Priyadarshan as he fires up a butt. “Can you use a Westerner here?” I ask seductively. He stares at me, smiling, nonplussed. “You know, a Western extra, hanging around the bar,” I continue more loudly, waving at the drinks. “No,” he says.

“What about later, tomorrow?”

He turns away.

I am bitterly, irrationally crushed. I walk outside, between the hangars, among the squatters and parrots. The fug of Bombay seems to have stretched its tentacles deeper into the hills. The dread-locked girl-wrangler emerges, talking on his cellphone. “No, Annabell’s in Goa,” he says. “You need four girls, but they are busy tomorrow, here.” I ask him if, as well as Russian girls, he handles Western actors. Patrick gives me the curious nod Indians use, a loose up-and-down-plus-sideways wobble like the head-motion of those toy dogs people put in a car’s backseat. “I’ll talk to Annabell,” he says, “she’s the cousin of my wife. You’ll get something for sure.” He smiles cheerfully. Anything can happen here.

#

The multiplex is a fairly recent phenomenon in India, where masala traditionally shows in huge, single-screen “hard-top” theaters. It enjoys tax-breaks the old theaters don’t, and it’s tempting to assume this is a hidden government subsidy for the educated elite because these modern honeycombs of new-car-smell and screening rooms are tailormade for Muppies; the Indians who talk perfect English and know Teesside and Teterboro as well as they do Mumbai; the Western-oriented, Mumbai Urban Professionals who comprise the smaller, more recherché audiences that supposedly lap up films in English—movies with less song and dance, with righteous roles for Westerners.

The sleek Inox multiplex downtown, on Nariman Point, is hosting the launch-party for Parzania. I gawk with the press, clutching a Kingfisher among the lights and hors d’oeuvres of the opening—observing once again the crab-mating lunges of the film hacks as they compete for closeness to the female lead, Sarika. Parzania’s subject is the Gujarat riots of 2002 during which Hindu nationalist mobs killed hundreds of Muslims and people perceived to be Muslims. The film is based on the true story of a Parsi family; Zoroastrians, not Muslims; who lost their son to the violence. The family itself, or what’s left of it, sits in the back row of the small theater, weeping softly. One key role in the film is played by an American, Corin Nemec, a scientology fan whose most visible role was in Stargate-SGI. I reckon his must be one of the sensitive New Age Western characters I have heard so much about.

The film’s director, Rahul Dholakia, tells me “The new audience is growing but it’s not where it should be, it’s going to take time.” Dholakia and Ketan Mehta are jumpstarting a studio that will produce nothing but this type of indie film. He put Nemec in, Dholakia says, because he wasn’t sure Parzania could be distributed in India because of its subject matter (the National Film Board tends to censor films that deal with touchy subjects) and therefore he might have to rely on foreign markets, for which an American actor would be a draw. Jag Mehra, who directed Provoked; starring Miranda Richardson and Robbie Coltrane as well as Aishwarya Rai; is more sanguine about the “new” package of audience, film, cosmopolitan parts. “There was a time when every producer had to sell to five territories: Bombay, Delhi-Uttar Pradesh [the “A” market]; Punjab, Rajasthan and Central Provinces, the East (including Bengal), and the South [including Kerala and Tamil Nadu]… “Distributors wanted different things,” Mehra continues. “Even after the film was done they would say, ‘Can’t we have a scene where a guy gets drunk and dreams of home, and you put in an Uttar Pradesh folk dance? You were trying to be everything for everybody.” These days, Mehra believes, the task of satisfying such a diverse audience has been taken over by television. “There is not a single folk festival in India that isn’t represented in a TV serial,” he says. Old-style masala is hemorrhaging popularity among the fifty percent of India’s population below age twenty-five; even in the provinces it’s dying. A new, younger market has sprung up, with loose cash and a more upscale taste in narrative¬¬, not only in India’s cities but among the well-paid desi living abroad; those NRIs, or “non-resident Indians,” who know the West and want, by virtue of how they live their own lives, to see stories that reflect the reality, not the shadows, of other lands, other peoples.

As I watch Parzania, though, I have doubts about this new market split, these pastel cross-cultural roles that might move Muppies. Nemec’s character is if anything too sensitive. He comes to Ahmedabad to research Ghandi in his adopted city and as sectarian stews reach boiling point he submerges in “country liquor,” the home-made sugarcane hootch of India. Public drunkenness is viewed here as a symptom of Western decadence, and Nemec’s character—whimpering, confused—strikes me as another stereotype: the Quiet American, well-meaning but clueless, who drags down the world with his involvement. His is cousin, if not brother, to a slew of dumb-foreigner clichés: vapid tourist, charas-addled hippie, Oxford-twit; that have colored Western roles in Indian cinema since the ‘70s.

#

I have attended a lot of launch parties by now. I even got my name mentioned (for an opening at Jahengir Gallery) in the Bombay Times; two lines that would have cost 50,000 rupees had I bought them. But one night when no parties are scheduled I go to see Salaam-e-Ishq. It’s playing at the Regal, where the touts hang out. The Regal is one of the original masala theaters, a twenties pile, all shit-brown inside, brown gloomy paneling, vast ochre orchestra with metal seats and quaint tan art-deco masks representing tragedy and comedy. Salaam-e-Ishq is four hours long. Supposedly it’s a remake of the Hugh Grant vehicle Love, Actually though I can detect little resemblance other than a large cast; it’s crammed with song and dance routines featuring the stars Salman Khan and Anil Kapoor plus a host of babes. Classic fare. The trailers proclaim: “Six different couples. twelve different lives… one common problem: love,” and the story lines are familiar; a married man tempted by a beautiful stranger, an eloped couple whose female half loses her memory. The production values are first-rate but otherwise Salaam-e-Ishq is put together loosely, like grandma’s custard: slack continuity, loose editing, untied emotions, dialogue in English thrown in randomly and without subtitles—as Hindi scenes are tossed into films in Tamil, Urdu, Bengali. Songs spring out of nowhere. This looseness is something that I, used to slick, fast Hollywood fare, at first found wearing. But after watching a slew of Hindi movies I have gotten used to it, and even started liking it; as when you loosen your belt for no good reason, and only then realize it was cinched too tight. The only offbeat facet here is Shannon Esra, an American actress who is the unlikely love interest of a taxi-wala played by Govinda. There aren’t many people in the Regal. I sit in the 70-rupee seats, toes practically touching the screen, surrounded by two dozen moviegoers, all male, aged between twelve and twenty-five. I suppose their few numbers might confirm what I’ve been told about the decline of old-style Bollywood; yet this group seems to make up for its small size by their clear love for every aspect of this flick. They call out to the actors, sing snatches of songs, gufffaw at the gags, slump distraught by tragedy. The older, wealthier crowd in the 100-rupee rows makes less noise but seems no less rapt. This style may be on its way out but, in the Regal at least, its fans have yet to hear the news.

#

Another night, another bash; this time I am invited by Gary Richardson. Gary is tall, blond, 50-something; good-looking in an all-American sort of way—he played football for UMiss and worked, he says, as a Vogue model. He is proud of a role he played in Costa-Gavras’ Missing, very conscious of how he looks. You might stow him in the cliché Gladstone: the table-waiting, monologue-mumbling, narcissistic Sandy Meisner disciple, similar to scores I’ve met in New York, were it not for three facts: he lives in India, he listens, and his judgments are sharp and ungeared to the drive of schmooze. We rickshaw to 11 Echoes, a trendy joint on Juhu Beach. Juhu is the Malibu of Mumbai. The club even looks Californian with dark beams and Spanish-style stucco, a balcony overlooking the invisible sea. This too is a launch party, for a pop CD by Sarika, a B-list actress. As Gary and I are let through security a crowd of flashes pop—at Gary, at me on the off-chance I’m someone newsworthy. “You see,” Gary says, clapping me on the shoulder, “you’re famous already.” Sarika is on the mike, thanking the Academy, and Gary is off, hanging his biceps on showbiz types, mugging for the cameras that follow. “I broke my neck in a fight playing a British general—the equivalent of Hitler—” in an Indian colonial epic, Gary told me earlier. To those who claim stereotypes are changing, he says, “I’d like them to say that in the same room with me.” White actors in Bollywood, according to Gary, are hampered in the same way black actors were in the U.S. before Sidney Poitier. That’s especially true when it comes to playing a white man dating an Indian woman. Richardson is married to an Indian, and he leans on this point several times. “I was just offered,” he continues, “a part in a movie by one of these guys, a good director, very hard worker: an actress comes into my hotel room, I see her, throw a fit … call her a prostitute.” The character, Gary adds, pressures the girl for sex; she rejects him in horror. Gary, for his part, rejected the role. “I said, ‘I’m not interested.’”

My pulse speeds up.

“I’m interested,” I tell him.

“You don’t mind being seen as a rapist?” Gary replies. “Cause every time they need a white rapist, they’ll call on you.” Gary gives me a lot of advice should I get this or any part. He says, Make sure I get a script before I get to the set because most films don’t have scripts; directors work from notes and make it up as they go. “You’ll be pulled into a scene with five minutes’ notice and told to speak these lines… written on a napkin in Hindi, it’s very hard for an American to speak Hindi. And make sure you get a song. That’s what’s important, it’s the song-and-dance they remember. People will stop me and say, not ‘I saw you in that movie,’ but ‘I saw you in that song sequence.’

“And ask,” he adds, “if you get a dressing room, for your own toilet.” Gary has been on shoots where everybody from producer to chai-boy is queuing to use his bathroom. “I don’t like it when a pretty girl comes in to use it and the bowl is full and she thinks it’s me.”

Watching Gary tower over smaller darker film people I feel collegial sadness on behalf of white actors like him, like me. The first major white presence in India film was female, because Hindi culture before 1947 considered acting an indecent job for women; a significant number of white women got work in the industry then. One of these white actresses, a half-Greek, half-Welsh stunt girl named Mary Evans, became the first female superstar in India under the stage moniker “Fearless Nadia,” a black and white version of a Charlie’s Angel. There were slow spells for white actors in the aftermath of independence, as the taboo against Indian actresses withered away. Partition was perhaps too close, the wounds unhealed, no one wanted to see flicks with whites playing, say, brutal British cops.

In the late fifties white actors played British scum--sadistic colonels, racist district commissioners--in a number of nationalist films. Another curious hiatus occurred in the sixties, when India and the USSR got hot and heavy politically, and several films featured Russian actors in positive roles.

Then, with the late sixties and seventies, came the next wave of white lowlifes—the drug smuggler, the racketeer, the corrupt captain of industry—roles (so the producer Pritish Nandy told me later) that arose, like fog from a cold sea, from the shortages and tensions of a frozen, statist economy, where contraband was a fact of life. “The theaters sold escapism,” Mehra comments, “and it killed movies.” Around this time Western flower children showed up, thirsty for gurus, and the Hindi screen reflected their presence with a clutch of dirty, barefoot drugged out backpackers. After the economy opened up in the nineties and especially during the last five years Indians started to feel self-confident about their role in the world and one would expect movies to reflect this change in the form of new, laudable Western roles: The Yank opening a call center in Bangalore; the US agent tracking radical Islamists in Kashmir. The role Madhur has for me is supposedly along those lines.

I have taken the number of the director whose part Gary refused; his name is Ananth Mahadevan, and he lives in Andheri, not far from Juhu. Gary is not sure if the shoot is still happening or when, so this all seems tenuous; nonetheless, for all of ten seconds, I feel guilty for selling out to stereotype. I stare toward the invisible horizon. Below me, on Juhu Beach, dozens of brightly lit stalls sell kolikata, a sweet-and-sour slushie. People move, as always, everywhere, dark shapes among the stalls, up and down the beach road, in and out of darkness, staring toward the bright lights and loud music of 11 Echoes then averting their faces to continue on their way.

#

I call Mahadevan on his cell—and get him first go. It’s a function of the openness, I think; try cold-calling a busy director in LA, see how far you get, see if you even get his number. Mahadevan is friendly, and asks me to send a headshot; but he is shooting three films at once and the scene I could work in--it’s part of a noir homage thriller called Agar, or If-- is well down his agenda. By the time he gets to it I’ll likely be back in New York. I should come watch him shoot anyway, Mahadevan says, he’s filming a TV scene in a week or so.

Another Gary suggestion: check with the Salvation Army hostel in Colaba, where backpackers hang out. Studio touts visit every day, he claims, trolling for extras. I go there the morning after 11 Echoes, but the desk clerk just shrugs: no.

I dial the numbers of my stable of touts: Kiran, Amjad, Imam, Warren, Jesse, Patrick. Imam has nothing but he puts me onto two more “agents” called Tiran and Hussein. Raja wants more cash, and insists that I meet him where he lives. He wigs out over the phone when I balk: “You’re gora, I’m Indian!” he screams, as if my thwarting him were proof of deep bigotry. “You’re gora I’m Indian!” I notice “Tiran”’s number is the same as that of “Kiran,” Jesse’s contact. Jesse, who works with Annabell, also works with Patrick and Imam. Annabell works with Ajay, a tout who like Darwesh hangs by the Regal. Amjad tells me the airport shoot has been canceled because of the elections. No one could score security clearance. Warren doesn’t answer. Kiran/Tiran hangs up on me. It strikes me that my lines of contact are starting to cross and cause short circuits. I have roped in so many touts that they are now starting to phone the same people on my behalf and everyone’s getting pissed off. I return to the Salvation Army that night and the clerk tells me there will be extra work tomorrow. “Eleven a.m., three people, for a Bollywood movie,” he says encouragingly. I don’t believe a word of it but I will show up anyway; it’s worth a try. On the Causeway that night I buy a little bronze statue of Ganesh, the elephant-god; he is known for supporting special projects. I place him on the table in my room, and place a slice of banana and a two-rupee coin at his feet. It’s worth a try, as well.

#

The next morning I show up an hour early at the Salvation Army. The same clerk tells me I’m too late; the three extras have already been chosen. I offer him money—this is, after all, India, where you bribe cops, politicians; why not the Salvation Army guy? He smiles sadly and closes his eyes. When the tout arrives—a good-looking kid in his twenties, called Vikaz—he tells me “I only need three people. For Bollywood film,” he adds, as if the blaze and glory of this might shut me up. He smiles in astonishment as I harangue him: I’m sure they can use a fourth extra, I’m an actor, I’ll work for free, I need the experience, for chrissakes just let me tag along! Mumbaikars, though big-city people, are like other Indians too polite to deal with this level of aggression. Finally, to shut me up, he makes a call, and tells me I can come and watch. I think, despite experience to date, that if I hang around long enough, maybe they will take me anyway.

My rivals for the part are an Italian couple in their late twenties, Joseph and Maria; and Simon, an Englishman, maybe twenty-five. He is of Iranian stock and looks it. We take the cattle-car local north. I find, out of nervousness, I cannot stop talking as we ride; showing off my train knowledge—Look, the big stink that suffuses the train after Mahim Junction is the Mahim River, an open cesspool next to Dharevi; the Mahim becomes the Mithi further north, which floods badly during the monsoon because its marshes were illegally filled by developers to build upscale malls. My companions smile at me. Future Studios is in Goregaon. It’s the stop for Film City, but the studio, a four-story rotblock, is in town on a rickshaw-choked road well shy of the hills. We climb to the third floor. A medium-sized loft holds three sets: a wedding banquet, a Mrs. Robinson-era living room, and a Western Union office. The crew is smaller than for Dhol; thirty people tinker, lounge, gawk monitors. A plump woman cuts us with sharpened eyes, talks in fast Hindi to Vikaz. My heartrate is over the speed limit. Vikaz said he would plead my case but now for the first time, standing next to these young Europeans, I am starting to realize how I must appear: balding, salt-pepper beard; even with makeup I can’t look younger than forty—the woman points at me. She points at Maria and Joseph. Vikaz turns to Simon. “She says, you look Indian.” He shrugs, and puts a consoling hand on Simon’s shoulder. I apologize to Simon, but inside my nerves fizz with exultation. I am in.

We are led to the top floor. A corrugated tin roof shields us from the sun. Wardrobe consists of a half-dozen trunks on which two people sleep. The ubiquitous Sai Baba gazes down on a props man who irons suits. Maria, Joseph and myself are fitted with Western-style office-wear. They serve us thali—dishes of chicken, chickpeas, beans in savory sauces, eaten with flat bread. Then Vikaz leads us downstairs to a dressing room with chipboard walls. I fidget; it might seem ridiculous but for the first time I am close to reaching the goal I came to India for: to act, even if only for a minute or two, before Bollywood cameras. And I try to remember what my drama coach taught: You over-act for theatre, underplay for film. Going through the range of hand and facial exercises to limber up, muttering soliloquies from MacBeth. After an hour Vikaz comes to fetch us; the plump AD explains our parts. Maria will be a Western Union cashier, Joseph will walk around behind her, looking busy with files; I will stand at the counter completing a transaction with Maria while the Indian star of this piece, a chubby, pleasant-faced actor named Dimesh Tohol, stands in line behind me. I will thank Maria, turn and walk way—well, all right; I add a line or two to amuse Maria, write out a note that reads “This is a hold-up,” making her smile. I’ll use the note as prop, something to stash in my jacket pocket, to keep my hands busy when I turn away. The set goes quiet. “Camera,” someone calls—“one, two, three, and—action.” On the first take, I say “I’ll take the loot later, thank you” to Maria and turn away, to find my exit blocked by lighting equipment. I stand there, confused. “Do it again,” the voice calls from behind the lights. The second time I walk under a black scrim and the director says impatiently, “He is bending down, why is he bending down?” They tell me to brush aside the scrim with my head. I work on relaxing, smiling at Maria, which is not hard, she has a face like June in Sienna; adding more words in front of my “thank you;” projecting my voice from the diaphragm, stashing the note with flair; losing my smile as I think of other things in turning. I feel better and better about all of this. OK it’s a nothing part but I’m doing it fine, I feel natural, convincing, I’m acting dammit! Acting in a Bollywood movie. Between takes I chat with the star, pro to pro; telling him, like any good thespian, about myself—I’ve trained, done TV, a little stage, written screenplays, I’m looking for more work here. Hoping he’ll have a connection. He seems interested, the Indian thing again, politeness plus appreciation of interest in his land. As we talk he passes from hand to hand a stack of British 50-pence pieces. I ask him about the coins. Why not use pound notes for a Western Union office, through which many of the 20 million NRIs send home thousands in cash? Dimesh holds up the stack in one palm. “This will become an animated character,” he says, “it jumps on my shoulder and then flies away. It will show how quickly Western Union sends money.”

I nod, and turn away. An ad, I’m thinking. It’s not a movie it’s a fucking advertisement. I tell Vikaz, “It’s an ad, isn’t it?” and he says, “it’s an advertisement for television.” “But you said, it was a movie,” I counter bitterly. His smile doesn’t alter by a fraction of a degree. When I tell this story later I am informed that the “Bollywood movie” line is a classic, obvious come-on line for touts. For now, though, I turn away, furious, disappointed, far more than I was over Dhol; that, after all, was a crapshoot, I had no right to expect anything from walking onto a set. I understand, from the power-level of these reactions, how deeply my gut is wound up in cracking, however marginally, the barriers that keep me from doing what I’ve come here to do.

#

It gets hotter. I spend more time in my room. Watching the fan. Listening to the crows, about which Mark Twain wrote, "[the crow sounds] like a low comedian, a dissolute priest, a fussy woman, a blackguard, a scoffer, a liar, a thief, a spy." Reading the papers. Shiv Sena has won big in local elections. It’s as if upstate New Yorkers—mostly white, Christian, suspicious of immigrants—had taken over the Queens Borough Council.

I make calls. I talk to Madhur. He tells me, talk to his publicist. His publicist says that because Madhur’s film is about to open the director won’t be able to see me in the foreseeable future. “But that’s what I told you two weeks ago,” I protest, “I should see him early, before he got busy.”

All this should trigger my depression reflex which by now is well honed but I find I’ve already discounted this news—the body-language was there, in its telephone version; the reluctance in Madhur’s voice long ago.

One morning my cellphone rings. It’s Amjad. He sounds excited. I think, to give him credit, he’s happy to bear good news instead of the usual nothing. “There’s a shoot,” he says, “they need someone this morning.” The pathetic excitement starts up, like granddad’s erection, valiant in the virtual certitude of its never going anywhere. “George,” Amjad says, “are you tall?” “Six foot two,” I answer breathlessly. “George,” Amjad continues, “do you have blue eyes?” “Well”—I’ll fudge this one, my eyes are green—“blue-green, sort of.” “Are you blond?” “No, but aren’t wigs”—“George,” he continues, “how old are you?”

This is no time for truth in advertising. “Thirty-eight,” I tell him firmly.

“Oh,” he says, sounding disappointed. “They want someone young, to be with a girl. Young, blond--heldy.” “What?” “Heldy.” “What is ‘heldy’?” “Heldy.” Amjad’s getting impatient. “Do you know a blond heldy guy, maybe twenty-five? Can you ask him?” “I don’t know anyone heldy,” I reply bitterly. He asks me to look on Colaba Causeway, he will give me a cut of his commission. He can’t find work for me but he wants me to be a tout. Covering the mouthpiece I shout at the walls, “I will not work as a tout!” Then, more calmly, I agree. Maybe if I call back in an hour without having found a young blond hunk they’ll have to take this aging, green-eyed, brown-haired, non-heldy gora—this Mumbai Humbert Humbert. I read papers for an hour, and call back. The studio has made other arrangements. I lie on the bed, listening to the crows jeer. I feel worse than I felt during my dark night in the Ghandi-killers hotel. Then defeat was a mere likelihood; now it’s a certainty, a black stain that easily soaks the rotten fabric of the rest of my life—my plays that never got more than a staged reading, my acting that went nowhere, my novels that missed the bestseller list by a spread the size of Manitoba.

Eventually I reach some sort of depressive plateau, of Buddhist acceptance; and here’s the difference between me and Sylvia Plath, or Hemingway, or Captain Smith of the Titanic; I am too ready to live with my shipwrecks. I get dressed and go out for chai.

In Colaba people start to recognize the gora who stay more than a few days. The souvenir sellers stop harassing you. Dimesh long ago quit trying to sell me maps. I get to know Harry Keys, who lives at a hotel down the street. He’s twenty-four, tall, fair-haired, blue-eyed—heldy. He graduated from Bathurst U. in Australia with a film degree and is perpetually amazed at how laid-back Indian film-making is. “All sorts of things we were taught as rules they break completely,” he says. “In the West, they have seven storylines, here they have three; seems very shallow at first, but now it just seems like fun.” Harry recounts an extra job he did when he came to Mumbai six months ago. The studio needed whites who could ride, to play British cavalrymen ambushing a group of Indian rebels plus a sleazy white renegade selling arms to the Indians. When he got to the location, near Pune, Harry found another nine white men who had all bullshitted their way into the job; “all babbling, ‘Who knows how to ride? Who knows how to ride?’ None of them did.” Harry, as it happened, grew up riding. They put him in the vanguard of the cavalry charge; he was to gallop through the gate of a castle they’d rented for the shoot. The first take went as planned. As he charged in the “rebels” aimed muskets and said “Pow, pow”—most Indian movies are dubbed. For the second take Harry galloped magnificently into the rebels’ lair, brandishing “a real sword with a proper edge… As soon as I got in the room this gunfire started all around, ‘ka-boom! They’d been loading the muskets with a sort of sticky gunpowder, they had little head-shaped charges which were exploding and spraying sparks. They’d stuffed the horses’ ears with cotton so they weren’t too bad but I was so scared I was squealing like a girl, (yelling) ‘Why the fuck didn’t you tell me?’ They all wet their pants laughing.”

That shoot had a contract Brit who also could not ride. He was to ride in front of Harry, firing a musket over his horse’s head as he galloped into the castle. “For the very first take,” Harry said, “they had loaded his musket four or five times—‘ba-BAM!’” The horse bolted, and the actor fell ass over teakettle into a crowd of villagers watching the shoot.

And then everything really fell apart. The Brit, suffering from what Harry calls “India shock—lepers, polio, ripoff, stench, cows, traffic”—went back to London. The producer wouldn’t pay the extras, who belonged to the Junior Artists’ union; a group which, like film financing in general, had links to Muslim organized crime gangs. Threats were made. The producer mysteriously “fell” from his hotel balcony. Harry has a contract, now, a real role in a proper film. His agent is my tout buddy, Warren. Harry’s a nice guy, and I’m not jealous of his good fortune—but I think, This could have been me, if only I’d been a bit younger. It crosses my mind that the real reason none of this is working for me is that I’m just too fucking over the hill.

But Harry has a girlfriend, she’s dancing in a shoot at the Kameland Studios in Jogeshwari, just south of Goregaon. And at this point I’m in a rut; failure or not, if I don’t get on the cattle-train to Movieland daily I don’t know what to do with myself. So it’s train-sutra, and rickshaw fumes, to a large compound outside Jogeshwari that resembles an old British cantonment town full of sun-stroked buildings labeled “Bank” and “Police” with dogs passed out in the heat and kids wandering and all of it surrounded by walls. Laura’s the girlfriend, from Sydney, trying out the dancing scene; her friend, Charlotte, a Brit, is a veteran. She, her husband and two kids live in a village outside Goa. She dances because she needs the cash and because she loves it. “You either hate it or you fall in love with the madness,” she says. “You handle it or go home straightaway.” Both women are in their twenties. They are dressed as Hawaiian hula girls. “It’s a film about cricket” Laura says, bemused, “but they didn’t tell us that for three days.” Jesse shows up, smoking, in dark glasses; he looks hung-over again. This is his gig. He herds the girls toward the soundstage, which, as with Studio 10 in Film City, looks like an abandoned industrial building until you get inside. Once there you’re in Blue Hawaii. Palm-frond huts, beach sand underfoot. Cartoons of cricketers adorn the walls of a “clubhouse.” Clearly we are supposed to be in the West Indies, whose cricket team, in real life, is currently on tour in India, raising much comment because Carribeans are so dark and Indians, conditioned since the earliest invasions, which tended to be run by lighter and lighter people, to equate darkness with fealty, are astounded that such dark people play such feisty cricket. I stand instinctively near the cocktail bar that seems to be de rigueur for song and dance sequences in Bollywood. Not a huge shoot this, only fifty people hanging around, but the singer for the sequence is Usha Uthup, a staple of the movie pop circuit. The stars are lower-A list—Kunal Kapoor and Rimi Sen (Naseeruddin Shah, a more powerful actor who had signed on for the film, pulled out to nurse his son after the latter fell out of the cattle train between two downtown Mumbai stations). Also they have roped in two famous cricket commentators to jive in the limbo dance. Most impressive of all, John Abraham—whom I last saw as husband of an amnesiac news anchor in Salaam-e-Ishq—is here to cameo in the video as a favor to his buddy, the director Milan Lutharia; Abraham was listed by FilmFare as the third most powerful male star in the Bollywood hit parade, and the top Christian actor in India. This video, titled “Wicket Bashao,” will likely be used as a trailer to advertise the film; and perhaps as the intro to the film itself, as title and credits roll. Usha belts out Hindi pop with a reggae beat. John Abraham wears a striped wifebeater. The same five bars, take after take, Abraham ejecting from the dance moves, laughing. The white chicks are not in this sequence but they must hang around anyway. I have no such obligation yet I hang by the bar as usual, waiting to be noticed. After another hour or so I leave, to go to another shoot; to sit on the sidelines again, and watch Ananth film something for television.

Sahara Studios: Andheri, next stop on the cattlecar, plus ten minutes by autorickshaw. I was supposed to show up at 12:30, but I am a half hour early. A spot boy leads me around back, over blasted concrete, through an alley of parked cars, past a thali buffet under the usual corrugated iron shelter, an old bitch licking her dugs in the shade—to a corridor full of props and ironing boards and wardrobe trunks. I sit on a prop, wishing I’d brought a book. The spot boy comes back. “Come,” he says, “come.” “No,” I tell him, “I’m early.” Ananth shows up, a smiling, clapping me on the shoulder. He’s an affable dude of 49, longish hair, army-olive shirt. “Come, George,” he says, “I want to use you for this scene.” Great, I think. My talents are finally in demand but for another TV shoot. It feels like fate, Greek drama, Kafka—push hard enough and you’ll never get what you want but the gods, to teach you a lesson, will offer you something different, useless, for purposes of irony. The soundstage in this case is the television version—a glassed-off studio with two standard TV vidcams and another, bigger camera. I smile indulgently: TV ads, TV shows, Foy can toss these off with ease. A well-groomed, handsome man in his forties, wearing a classy suit, sits at an announcer’s desk on the soundstage; a logo to one side reads “The RKB Show.” Ananth introduces the anchor as Rajiv K. Bajaj—his show, the director says, is the equivalent here of Jay Leno. Rajiv will be interviewing me briefly, just before a news segment. “What is he interviewing me about?” I ask as spot-boys adjust my clothes and fit a Lavalier. “Anything you want,” Ananth says, checking the cameras. “You can say anything.” “Look,” Rajiv says, “your name is French, right? I will ask you about your connection to that general at Quebec.” “Huh?” I say. Already Ananth and his crew have moved behind the cameras. Lights glare. Rajiv is straightening his tie, clearing his throat, staring at the lens. “George, look at the camera on the right,” he suggests, and then Ananth is saying “Three, two, one, and—action.”

It’s weird how those words work to silence noise, throttle up attention, jizz the nerves. They’re the password to story, I reflect, of whatever nature. Rajiv is into his spiel though, and as stories go this one is pretty pedestrian. I am still nervous about exactly what the hell I’m supposed to say to the Hindi Jay Leno, who is now introducing me as “a famous writer from New York City.” Rajiv turns to face me. “Your name is French, are you a relation to that famous French general from the Battle of Quebec, the battle of the Plains of Abraham?” What? I’m thinking, that was Montcalm, he got offed at the same time as Wolfe; two aristos croaking to claim a colony on a freezing field two and a half centuries and what seems a million miles from the sweating roaring blast-through of Mumbai. “Uh, actually,” I answer despairingly, doing my best to appear calm before the dead black eyes of the cameras, in the face of what suddenly seems like utter weirdness--Rod Serling’s about to show up at Ananth’s left, smoking and intoning “An apparently innocuous TV interview fades out to … the Twilight Zone.” “I mean there are two branches of my name, they’re both French, but one was, uh, French mercenaries who went to Ireland because, because they all hated the British. I mean my side stayed in France;” I’m warming to my genealogy now but in this second a man hustles up to Rajiv and slips him a note. Rajiv reads the note, turns to face the big camera, his face grim. “We interrupt this show to bring you an urgent news bulletin.” “Cut!” Ananth calls. “Let’s do it over,” Rajiv says. “OK,” Ananth agrees. “Give George some more lines,” Rajiv suggests. “Take Two,” Ananth says. I’m staring at them both, wondering what kind of bizarre Bollywood—or Tollywood as TV-land is known here—journalism is at play here; what species of urgent news bulletin will show up impromptu in what is clearly not a live segment. “You see,” Ananth says, coming over to me, “after this Rajiv’s face comes on the screen at the airport. He says the killer has been spotted there, at the airport. Which warns him, so he flees.” I stare at him. My mouth is open; I may be drooling, I wouldn’t know. “You-you mean,” I stutter, “this isn’t really a TV show?” “Yes,” Ananth says, “It is in Agar.” “A film,” I whisper. More loudly: “This is a film.” “Of course,” he replies, turning away now. “The noir film I told you about.” “That was good,” Rajiv tells me encouragingly, fiddling with his tie once more. “I’ll ask you about your family again, and you tell me about them.” “Montcalm,” I whisper. Already I am wondering what I can do to liven this up. Am I a smooth habitué of the interview circuit, the kind who trades quips with “Jay” and mentions his new book at least three times? I try on my face the kind of self-satisfied smirk such a character would wear. I look straight at the big camera. “Three, two, one,” Ananth calls. “And—action.”

#

I return to Goregaon that night. I’ve been wanting to visit a theater outside central Mumbai. Goregaon boasts the Anupam Cinema, a monstrosity of formed concrete layers, abstract shapes, all pasted together with concrete and pea-colored paint; an acre of bad sixties architecture, similar in concept to the living-room set at Future Studios. I am hoping to see Madhur’s just-opened film, Traffic Signal, and in so doing get a sense of how people in a low-rent district lap up the new cinema; Traffic Signal is an unusual show, without songs or dances, based on the lives of thieves, mafia types, con artists, beggars and other types living near one Mumbai traffic light. The Madhur film has inexplicably been canceled; when the lights dim what ghosts up on the screen is a fifth-rate Hong Kong kung-fu flick, dubbed in Hindi. The audience—identical in age distribution to that in the Regal—is sparse; it and seems to like the choreographed, absurdist violence, but is not involved the way the Salaam-e-Ishq audience was involved. My mind, bored by the clueless plot, strays, and I find myself wondering if the much heralded split between the new films, the ones with more Western roles than most, versus the old masala that this audience might prefer is not a symptom of a deeper division. Masala was the old Mumbai, or India, swirling, vast, integrative—there’s an exchange, ironically in Parzania, between Corin Nemec and his Indian mentor that struck me as typical of the other kind of movie, with its something-for-everyone characters, and of this city: “You have so many gods, which one can you believe in?” the American wails. “You have to believe in all of them,” the Indian replies, neatly spelling out the “throw it all in” gene-sequence of masala. Is the rise of these new films nonetheless a sign of what’s to come—a growing split between the new, information-age, middle-class and English speaking India, and those left behind; between the one million people in IT, and the 1.9 billion who can’t find or maybe even qualify for computer-related jobs. If India, the world, can keep growing, avert disasters ecological, political, economic, maybe the masala fans, as they join the world’s swim, will start to appreciate English actors in non-musical shows. And if not?

I leave halfway through the film and train-sutra back downtown. Unable to relax, I don’t go back to my room and walk instead through the Koli shantytowns. It is late but time has no meaning here or elsewhere in this city; at noon, at midnight, at four in the morning the trucks rickshaws bullock carts are always on the move and you see people walking, buying, sleeping, selling at any hour. Here infants and dogs are sacked out as rats scurry between them in the dirt and people stroll in the thin alleys, move in the lit openings of their makeshift rooms. Women bring offerings to the Sai Baba shrines. I look for televisions; there are some, by no means many, maybe every tenth doorway or window. Boys, assuming I’m lost, give me directions I can’t understand. They smile as I walk off the wrong way—astonished, perhaps, as much by my utter irrelevance to their lives as by my ignorance of these streets. Lost near Sassoon Dock I am chased off by a drunk, a dog, and a naked man, all barking furiously at the intruder; unaware that he is an actor in a Bollywood movie, part of a myth they can in some fashion hang their dreams upon. I turn and head back to the Causeway.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete